|

THE EASTER OFFENSIVE OF 1972 by Lt. Gen. Ngo Quang Truong Published by U.S. Army Center Of Military History

Contents

Glossary

THE EASTER OFFENSIVE OF 1972

CHAPTER I

Introduction

From Insurgency to Conventional warfare

And so, within two weeks beginning on Easter day, large

conventional battles were fought simultaneously on three major

fronts that pitted a total of ten NVA divisions against an

equivalent number of ARVN forces. For the first time, almost the

entire armored force of North Vietnam was thrown into the battles

along with a significant increase in heavy artillery support. This

was the largest offensive ever launched by the Communists against

the Republic of Vietnam since the beginning of the war and because

of enemy timing, it was quickly called the Easter invasion.

Judging from the size of forces committed and the tactics employed,

this offensive represented a radical departure from the methods of

warfare the Communists had historically used in their attempt to

conquer the South.

The political events in 1963 and the ensuing turmoil during 1964, however, seriously impeded RVN military efforts and security deteriorated rapidly. In the country side, increasing numbers of strategic hamlets were penetrated and overrun by the Viet Cong. Friendly losses in weapons increased at an alarming rate and several territorial force units in remote areas just vanished in the face of enemy pressure.

By late 1964, Viet Cong battalions had been grouped into regiments

and regiments into divisions. Several large scale battles were

fought during this year; the most notable was the attack conducted

by the VC 9th Division against the Catholic village of Binh Gia,

east of Saigon, at year 5 end. During this battle, the enemy

ambushed and annihilated an ARVN ranger battalion and a marine

battalion. He also inflicted severe losses to an ARVN armored

force which came to their relief. This was the first time enemy

forces had ever remained on the battleground in sustained combat

for several days. To both sides, it was an event of significant

importance. The Communists considered this effort the first step

toward the so called "mobile" or final stage of their

revolutionary warfare. To South Vietnam, it was the beginning of a

military challenge that would be long and difficult.

By mid 1965, ARVN forces were suffering losses which statistically amounted to an average of one battalion and one district town per week. The military situation was deteriorating at such an alarming rate, the United States deemed it necessary to commit its combat troops to fight the ground war to forestall the collapse of South Vietnam. Soon to be followed by combat units of other Free World countries, U.S. forces began' to conduct search and destroy operations in August 1965. Still, the ARVN suffered another major setback at the hands of the same 9th VC Division when it reappeared at the end of the year and badly mangled the 7th ARVN Infantry Regiment in the Michelin rubber plantation north of Saigon. As a result of the arrival and direct participation of U.S. and Free World military forces, the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces (RVNAF) gradually regained balance. During the years 1966 and 1967, both U.S. and RVNAF units increased and expanded their offensive operations. These operations were designed primarily to destroy the enemy's bases and strongholds, clear the populated areas from his encroachment, and create a favorable setting for pacification and development. War Zones C and D, the enemy1s thus far impenetrable strongholds north of Saigon and his other base areas west of Pleiku, Kontum and north of Quang Tn became targets for repeated attacks by U.S. and RVNAF units.

During this period, Communist forces operating in South Vietnam

not only lost their initiative but were driven, unit by unit, away

from populated centers and major areas of contest. Gradually,

local Viet

During 1967, the enemy endeavored to continue some of his initiatives in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and in other remote areas along the national borders. But deep inside South Vietnam, there were absolutely no significant enemy activities or accomplishments. To redress this deteriorating posture, it was obvious that a major shift in effort would be required. North Vietnam leaders came to the conclusion that only a major, decisive offensive could help him turn the tide around. Toward the end of 1967, intelligence reports began to indicate that there were significant infiltration of men and materiels and large troop movements down the Ho Chi Minh trail system and along enemy lines of communication inside South Vietnam. This information was coolly received by RVNNF authorities, more as a routine matter than a cause for alarm. Cautious measures were duly taken in the same old pattern of years past, focusing on remote areas and the countryside rather than on the cities and urban centers. As usual and routinely, a declared truce was planned during the Tet holidays commemorating the Vietnamese lunar calendar New Year.

Suddenly, the Communists initiated a general offensive, striking

at almost all major cities and urban centers across the country.

This occurred while the majority of Vietnamese, civilian and

military alike, were celebrating the Tet amidst the deceptive

quietness of the truce. From the very beginning of this offensive

the enemy committed an attacking force of such proportions as

never before encountered during the entire war, estimated at 84,000

troops including local forces. Attacks by fire, ground assaults,

and sapper actions were repeatedly launched against 36 of the 44

provincial capitals, 5 of the 6 major cities and 64 of 242 district

towns of the RVN. This was the first time that our South

Vietnamese urban population had ever experienced the hazards of

real war. Although taken by surprise, the RVNAF reacted swiftly

and forcefully. With the support of US and Free World forces,

In Saigon, despite their ability to penetrate the city without being detected and the fact that the defenders were caught unaware by their attacks, Communist forces were unable to occupy any key installation very long. But they clung stubbornly to the densely populous areas of Cho Lon. It took our cautious soldiers and the police forces nearly two weeks to clear the last enemy troops from the city. At Hue after penetrating the city, Communist forces succeeded in occupying mo8t of it, particularly the old citadel, and lay siege to several military installations. During that time, they murdered more than 3,000 defenseless servicemen and GVN civil servants and cadres stranded in the city. This 26-day battle for the control of Hue resulted in extensive destruction within the city and left 110,000 of its inhabitants homeless. While battles were raging fiercely in cities and towns across the country, on 7 February 1968, the enemy launched determined attacks in the highland area around Khe Sanh Base near the borders of Laos and North Vietnam. This base including its airstrip, was defended by a reinforced U.S. marine regiment and an ARVN ranger battalion. Despite the enemy's repeated assaults and continuous attacks-by- fire, Khe Sanh Base held firm under siege. North Vietnam's apparent design to stage and repeat a Dien Bien Phu type victory was soundly defeated by the overwhelming firepower of US forces.

The first phase of the enemy's general offensive of 1968 thus

ended in dismal failure. The price he paid for it was

excruciatingly high. Not only had he lost over 50,000 men he had

also sacrificed the elite troops of his local force in suicidal

attacks. However, by bringing war into the big cities, the enemy

had wrought havoc and created a resounding shock. His action also

drew RVNAF and Allied forces away from the rural areas for the

protection of urban centers. To deepen the psychological impact,

particularly on the United States, the enemy continued his

offensive campaign of 1968 with

After their military defeat during 1968, Communist forces in South Vietnam went through a period of decline. Despite attempts at resurgence which materialized with a country wide offensive on 23 February 1969 and during the following two years under the form of seasonal "high point" activities, they never recovered enough to engage in large scale and sustained attacks. As a result of his local force units being severely decimated during 1968, the enemy also had difficulties re-establishing his system of communication and mutual support between border base areas and feeder zones adjacent to urban centers. Therefore, NVA main force units in the South were virtually cut off from their usual source of supply and local guides, which were considered indispensable for effective operations. The big challenge having been overcome, the RVNAF became more self assured. With the strong support provided by United States and Free World Military Assistance forces, the RVNAF stepped up their operational efforts during 1969. The resulting achievements in pacification were never so good. Not only were the enemy's safe havens along the border continually under attack, his base areas inside South Vietnam, both those straddling infiltration routes and others adjacent to populous centers were also effectively "cleared and held." In August, 1969, as a result of a new policy U.S. and FWMA forces began to withdraw from South Vietnam. To help the RVNAF develop their self contained capabilities for combat operations and pacification support, the United States undertook an accelerated program of improvement and modernization which was called Vietnamization.

All of these developments edged the Communists toward relying more

on conventional methods of warfare, a radical departure from the

kind of attrition warfare they had fought during the years prior to

1968. During 1970, after greatly reinforcing his forces in the

South, the enemy made plans for large scale attacks. But these

plans were preempted

Following up on their successful exploits in Cambodia, in February 1971, the RVNAF launched a large scale but limited offensive into lower Laos with substantial support in firepower, airlift and logistics provided by the United States. Code named LAM SON 719, this operation was designed to interdict the enemy's north-south infiltration routes and to destroy his supply bases in the Tchepone area, a vital communication hub of the Ho Chi Minh trail system. ARVN forces committed in the operation were all elite, combat proven units of the RVNAF - the 1st Infantry, the Airborne, and the Marine Divisions. But they could not achieve all of the objectives contemplated, partly due to the forceful reactions of the enemy who for the first time employed tanks and heavy artillery in battles with success, and partly due to some tactical blunders on our part. This experience seemed to reinforce the enemy's belief that with his modern weapons, he coul4 defeat South Vietnam's armed forces, and consequently, the war could be ended by a military victory once U.S. troops had been withdrawn. Further, he believed that military victory could only be achieved by a conventional invasion. To prepare for his invasion, North Vietnam requested and received huge quantities of modern weapons from Russia and Red China during 1971. These included MIG-21 jets, SAM anti-air missiles, T-54 medium tanks, 130-mm guns, 160-mm mortars, 57-mm anti-aircraft guns, and for the first time, the heat-seeking, shoulder fired SA-7 missiles. In addition, other war supplies such as spare parts, ammunition, vehicles and fuels were shipped to North Vietnam in such amounts as never before reported during the previous years of the war.

Despite this growing military threat, the United States and other

Free World allied countries maintained their disengagement policy

and

General Character of the Easter OffensiveIt was not by simple coincidence that Hanoi selected the code name Nguyen Hue for its Easter invasion of 1972. Nguyen Hue was the birth name of Emperor Ouang Trung, a Vietnamese national hero who in the year of the Rooster (1789) maneuvered his troops hundreds of miles through jungles and mountains from Central to North Vietnam, surprised and attacked the invading Chinese in the early days of spring and dealt them a resounding defeat in the outskirts of Hanoi. In early 1972, Hanoi apparently wanted a repeat of this historic exploit in the other direction. But Hanoi failed to achieve the surprise that constituted the decisive advantage enjoyed by Nguyen Hue. By the end of 1971, evidences of North Vietnam's preparations for the invasion of the South had appeared from a number of sources. Notably, divisions of the NVA general reserve were moving south and a "logistics offensive" was underway in the Southern region of North Vietnam. In early December, the Joint General Staff began sending warnings to military region commanders advising them to be prepared for a major enemy attack during early 1972.

The most difficult part of the estimate concerning the enemy's

obvious intention to attack was the timing. In an early warning,

ARVN intelligence revealed that the enemy had the capability for a

major offensive and forecast that he would probably initiate the

attack sometime before the Tet or in late January. Nothing

happened. Subsequently, a second estimate, based upon evidence of

increased preparations in the B-3 Front, foresaw the possibility of

attacks during the Tet

Although there was general agreement in the intelligence community - Vietnamese as well as American - that an offensive in early 1972 was highly probable, some observers of the Vietnam scene, perhaps those not as well informed as those of us privy to the most reliable estimates, were influenced more by what seemed to them to be the illogic of a major North Vietnamese attack at this time. They reasoned that to ensure victory, North Vietnam would wait until 1973 when most, if not all, U.S. forces would have been withdrawn according to plans. It would be impossible then for the United States to reintroduce troops and the chances of U.S. intervention by air would also diminish. To Hanoi, however, 1972 was apparently just as good an opportunity since by the end of January, U.S. combat strength in South Vietnam would have been reduced to 140,000 and should reach below 70,000 by the end of April. By that time, the remainder of U.S. forces would consist merely of three combat battalions and some tactical aircraft and helicopters, a combat force no longer considered significant. In a certain sense, this residual force would make 1972 look even more attractive in Hanoi's eyes because if it could achieve a military victory, the U.S. would certainly have to share in South Vietnam's defeat. Moreover, if the Vietnamization program and RVN pacification efforts were permitted to continue successfully and without interruption throughout the year, the military conquest of South Vietnam might well be much more difficult. To Hanoi, therefore, 1972 was the year for action.

With regard to timing, North Vietnam's genuine problem was

probably to launch the invasion at such a time as to be neither too

far ahead of the U.S. presidential elections in November 50 as to

enhance its political impact nor too late into the dry season when

torrential rains by late May could seriously impede movements on

infiltration routes

But where would these attacks take place and what objectives did the enemy have in mind in 1972? To veteran military intelligence officers, these questions were not very difficult to answer. Again, based on past activity patterns and geopolitical goals of the enemy they would predict that his actions would probably occur in areas where NVA main force units and their supplies were concentrated such as in the DMZ, the Tri-Border area, or in those areas adjacent to such well established base areas as War Zones C and D, Dong Thap (Plain of Reeds), and U Minh. More precisely, current intelligence on the disposition and deployment of NVA main force units at the time allowed us to estimate that in MR-l, there would be a two pronged attack, one to be conducted by the NVA 304th and 308th Divisions from the direction of Khe Sanh against Qnang Tri, and the other, an eastward effort by the NVA 324B Division from the Laotian border against Hue. The enemy's apparent objectives were to occupy Hue, the ancient capital, and threaten the harbor and airport of Da Nang, 60 miles to the south.

The second enemy effort would be directed against the highlands of

MR-2 with Kontum as a primary target. This attack was to be

conducted by two NVA divisions, the 2d and 320th. Farther to the

south, in MR-3, it was possible that, in concert with the total

effort, the three enemy divisions in that area, the 5th, 7th, and

9th, would launch attacks

Although the three areas of the enemy's major concentrations -- northern MR-1, Kontum, and north of Saigon - were clear indicators that the heaviest attacks would occur in these regions, it was impossible, on the basis of available intelligence, to determine the priority the enemy assigned to the three objective areas. Neither could we tell which attack would be launched first, or if they would occur simultaneously. The real issue, as far as the RVN was concerned, however, was not so much the enemy 5 choice of primary effort or his timing as the proportions of his offensive. It was fairly easy to predict that the invasion would dwarf all other previous attempts in scale; it was also possible to predict with reasonable accuracy how much combat force the enemy was going to commit in this invasion initially -- which in all probability would consist of at least 10 divisions and supporting elements or a total of about 130,000 troops. But no one was able to conclude at that time exactly how much reinforcement these initial forces would eventually receive in the next stage and ultimately what size the NVA total commitment would be. Obviously, it was also equally impossible to tell how long the offensive would last and finally, how much sacrifice the enemy would be prepared to accept to ensure his victory. These were the questions left unanswered until after NVA troops crossed the DMZ on 30 March1 1972.

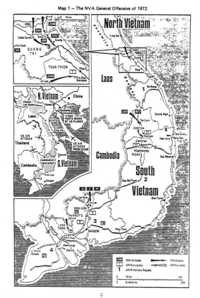

The enemy's Nguyen Hue campaign finally materialized under the

form of an unprecedented, conventional invasion with three large

spear heads or efforts. The first effort was conducted across the

DMZ in northern Quang Tri Province; it was combined with another

effort driven eastward in the direction of Hue City. The second

effort, initiated a few days later, struck into Binh Long Province

in northern MR-3 from the Cambodian border. The third effort,

which was conducted after

North Vietnam, as it turned out, was committing its entire combat force --14 divisions, 26 separate regiments, and supporting armor and artillery units -- into the battles, except the 316th Division which was operating in Laos. The fierceness of this all out invasion turned parts of South Vietnam into a blazing inferno. The enemy's classic frontal assaults which spearheaded these battles proved tremendously effective, at least during the initial stage. Our strong points just south of the DMZ, a responsibility of the ARVN 3d Infantry Division, were unable to hold more than three days under repeated artillery barrages and vigorous attacks by enemy armor and infantry forces. After a month of resisting, our 3d Division and the defending forces of northern MR-i disintegrated; Quang Tri city fell into enemy hands. Areas north of Binh Long and west of Kontum were also under his control and the cities of An Loc and Kontum were under heavy attack. It was only three months after the outbreak of the invasion that ARVN forces regained their poise supported by powerful and effective U.S. tactical air and naval gunfire, and began the counteroffensive.

The ARVN counteroffensive was fairly effective. Not only did it

completely stall the NVA invasion on all major fronts, it also

succeeded in recovering part of the lost territory, including the

provincial capital of Quang Tn, the first ever to fall into enemy

hands. This feat alone, notwithstanding the heroic siege of An Loc

and the unyielding defense of Kontum, eloquently testified to the

combat effectiveness of the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces and

offered proof of the success of the Vietnamization program. The

biggest challenge had been met, our combat maturity had been

proven, and the South Vietnamese people's

The battles fought during the blazing red summer of 1972 marked a turning point in the Vietnam war. For the first time, Communist North Vietnam realized it had no chance of a military victory while the U.S. still provided the South with air support and adequate logistics. It was finally compelled to accept a cease fire.

The battles of the Easter offensive, the gains and setbacks, and

the strengths and weaknesses of both sides will be presented and

critically analyzed in the following chapters.

|