|

THE EASTER OFFENSIVE OF 1972 by Lt. Gen. Ngo Quang Truong Published by U.S. Army Center Of Military History

Contents

Glossary

THE EASTER OFFENSIVE OF 1972

CHAPTER II

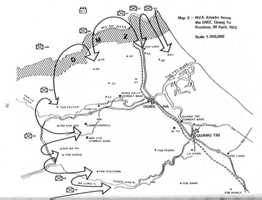

The Invasion of Quang Tri

Situation Prior to the OffensiveMilitary Region 1 consisted of the five northern provinces of South Vietnam stretching from the Demilitarized Zone in the north to Sa Huynh at the boundary of Military Region 2 to the south. Most of the area was made up of jungles and mountains of the Truong Son range which sloped down from high peaks along the Laotian border toward the sea. Between the piedmont area of this mountain range and the coastline lay a narrow strip of cultivated land along which ran national Route QL-l. This was where most of the local population lived. The two northern provinces of MR-l, Quang Tri and Thua Thien where Rue was located, were separated from the three provinces to the south, Quang Nam, Quang Tin, and Quang Ngai, by an escarpment which projected into the sea at the Hai Van Pass. Da Nang, just south of this pass, was the biggest city of the region and the location of the Headquarters for ARVN I Corps. It was also a major port capable of accommodating sea going vessels. A lesser port, Tan My, northeast of Hue, served as a military transportation terminal for shallow draft vessels supplying ARVN units in northern MR-l. It was in this area that several major battles of the 1972 Easter invasion were fought.

By March 1972, almost all U.S. combat units had redeployed from MR- l. The single remaining unit, the 196th Infantry Brigade, was standing down and conducted only defensive operations around Da Nang and Phu Bai airbases, pending return to the United States. Ground combat responsibilities were entirely assumed by ARVN units with the support of U.S. tactical air and naval gunfire and the assistance of American advisers In the area north of the Hai Van Pass, where 80,000 American troops had at one time been deployed, there were now only two ARVN infantry divisions supported by a number of newly activated armor and artillery units. Total troop strength committed to the defense of this area did not exceed 25,000.

The backbone of I Corps forces which were responsible for the

defense of MR-l consisted of three ARVN infantry divisions, the

1st, 2d and 3d, the 51st Infantry Regiment, the 1st Ranger Group

(with 3 mobile and 6 border defense battalions) and the 1st Armor

Brigade. Other combat forces organic to I Corps included the 10th

Combat Engineer Group and corps artillery units. The territorial

forces of MR-l, whose key combat components were the six Regional

Forces (RF) battalions and company groups, also contributed

significantly to area security in all five provinces. I Corps,

commanded by Lieutenant General Hoang Xuan Lam, exercised control

over all regular and territorial forces assigned to MR-i. General

Lam, an armor officer, was a native of Hue.

(1)

The 3d Division was generally responsible for the province of

Quang Tri. Its headquarters, under the command of Brigadier

General Vu Van Giai, former deputy commander of the 1st Division,

was located at Quang Tri Combat Base. Two of the division's three

regiments, the newly activated 56th and 57th, were deployed over a

series of strong points and fire support bases dotting the area

immediately south of the DMZ from the coastline to the piedmont

area in the west. The 56th Regiment was headquartered at Fire

Support Base (FSB) Carroll while the 57th Regiment was located at

FSB Cl. The 2d Regiment, which was formerly a component of the 1st

Division, occupied Camp Carroll with two of its battalions at FSB

C2. Camp Carroll was a large combat base

In addition to its organic units, the 3d Division exercised operational control over two marine brigades of the general reserve, the 147th and 258th, which were deployed over an arched ridge line over looking Route QL-9 to the west and the Thach Han River to the south. The 147th Marine Brigade was headquartered at Mai Loc Combat Base while its sister1 the 258th Brigade was at FSB Nancy. These marine dispositions formed a strong line of defense facing west, the direction of most probably enemy attacks, and provided protection for the population in the lowlands of Quang Tri. Under the supervision of the 3d Division, but not directly controlled by it, were the regional force elements which manned a line of outposts facing the DMZ from Route QL-l to the coastline. These elements were under the command of Quang Tri Sector and Gio Linh Subsector. South of the Quang Tri - Thua Thien provincial boundary and north of the Hai Van Pass, lay the tactical area of responsibility (TAOR) of the 1st Infantry Division commanded by Major General Pham Van Phu. Its primary mission was to defend the western approaches to Hue. It deployed the 1st Regiment at Camp Evans, the 3d Regiment at FSB T-Bone and the 54th Regiment at FSB Bastogne. The division headquarters was located at Camp Eagle, just south of Hue. The 7th Armored Cavalry Squadron, organic to the 1st Division, was located with the 1st Infantry Regiment at Camp Evans.

The three provinces of southern MR-i, all located south of Hai Van

Pass, were the responsibility of the 2d Infantry Division,

commanded by Brigadier General Phan Hoa Hiep. The division

headquarters was at Chu Lai in Quang Tin Province where the 4th

Armored Cavalry, organic to the division, was also located. Each

of the division's three regiments was assigned to a separate

province. The 5th Regiment operated near Hoi An in Quang Nam

Province; the 6th Regiment was headquartered

Among I Corps forces, the 1st Armor Brigade -- which was to play an important role in the battle for Quang Tri -- had not been involved in actual combat for more than a year. The brigade's last combat action took place during the LAM SON 719 operation in lower Laos from February to April, 1971 where it had suffered high combat losses. Despite extensive reorganization and refitting efforts, which included the activation of the 20th Tank Squadron, our only unit equipped with M-48 medium tanks, the combat worthiness of the 1st Armor Brigade was still untested and difficult to evaluate. While the 1st and 2d Infantry Divisions were thoroughly combat proven, the 3d Infantry Division was just organized as a unit on 1 October 1971. Two of its three regiments, the 56th and 57th, had been formed and deployed in forward positions along the DMZ barely three weeks before the invasion took place. At that time, the division did not have its own logistic support units and its artillery was still receiving equipment. But the overall status of the division seemed to be fairly good, the morale of its troops was high, and its unit training programs were on schedule. The division commander was professionally capable and highly dedicated to his job; his leadership inspired confidence among subordinate units. The division was still short of many critical items, especially signal communications. Despite this, the division endeavored to develop its combat capabilities through uninterrupted training which appeared to be quite effective. However, in no way could have the 3d Division be considered as fully prepared to fight a large, conventional action.

The two marine brigades which were placed under the operational

control of the 3d Division were in every respect thoroughly combat

effective. They were both at full strength, well equipped and well

supplied through their own channels. But while their reputation as

elite units of the RVNAF was solid and their combat valor held in

high

As far as I Corps Headquarters was concerned, it had never really directed and controlled large, coordinated combat operations except for the unique case of LAM SON 719 during which it operated as a command post in the field for the first time. Although the I Corps staff excelled in procedural and administrative work and was effective in the operation and control of routine territorial security activities, it lacked the experience, professionalism and initiative required of a field staff during critical times during battle.

During the month of January 1972, orders were issued by I Corps to

all major subordinate units, alerting them to be prepared for a big

enemy offensive during the Tet holidays. This was done merely to

comply with orders from Saigon since the I Corps commander saw

nothing to indicate an imminent major enemy offensive. Although

Saigon had concluded that the preparation for movement and combat

that had been detected among the NVA divisions north of the DMZ

were reason enough to alert the command, these divisions were still

far from the line of contact and General Lam saw no cause for

immediate alarm. He took cognizance of the enemy's logistical

build up in the area north and west of the I Corps defenses, but

still he believed that the Communist Tet actions

And so, appropriate measures were taken by I Corps forces to counteract the enemy1s harassment activities rather than fully brace themselves for a major enemy offensive. ARVN units indeed reacted effectively to enemy initiated activities throughout MR-l, and the Tet holidays passed in relative calm. Intelligence officers and tactical commanders, meanwhile, closely monitored and waited for signs of movement of NVA forces. Their correct prediction of the enemy's scope of activities for the Tet period reinforced their confidence that he would probably not depart from his established pattern of making deliberate deployments, which would be detected, prior to launching the offensive. By February, this assessment of the situation gained further credibility when it was revealed that the NVA 324B Division was moving into the A Shau Valley in western Thua Thien Province. This was a familiar and often used staging area for this enemy division to launch attacks against Hue. The 1st ARVN Infantry Division deployed accordingly to preempt this move and clashed violently with NVA units along Route 547 west of Hue in early March. What remained to be confirmed as definite indications of the predicted offensive in MR-l was the movement of elements of the NVA 304th and 308th Divisions into western Quang Tri Province. While there were unconfirmed reports that the 66th Regiment of the 304th Division was in the Ba Long Valley near FSB Sarge, the location of the other two regiments the 9th and 24th, were unknown at that time. They were believed to be just north of the DMZ as was the entire 308th Division.

General Lam did not believe in the theory that the NVA might

attack across the DMZ although the danger of such an attack had not

been ruled out; this had never happened before. This no-man's land

was mostly flat, exposed terrain, unfavorable for the maneuver of

large

When confronted with the possibility of a NVA drive across the DMZ, General Giai, commander of the 3d Division, had the same reaction as General Lam. He, too, believed that any large attack would come from the west although he did not reject completely the possibility of an attack from the north since he knew there were indications that the enemy had brought surface-to-air (SAM) missiles, additional 130-mm field guns, ammunition and armor in the area just north of the DMZ, and beginning on 27 March there was a marked increase in indirect fire attacks against the division's fire support bases in the DMZ area. But General Giai was facing more pressing problems in his area of operation (AO) at that time. His primary concern was to consolidate his recently occupied defensive positions to the west, train and continue to prepare his division for the enemy offensive. Nevertheless, he and his staff were continually debating the problem of dominant terrain features, the enemy's most probable course of action, the disposition of his units, the configuration of their defense positions and above all, how to employ his forces effectively in the event of an enemy offensive.

While his staff was developing comprehensive plans for the defense

of the division's area of responsibility, General Giai initiated a

program of rotating his units among the regimental areas of

operation in order to familiarize them thoroughly with the terrain

and to eliminate the "firebase syndrome" among his troops. In

accordance with this program, on 30 March the 56th and 57th

Regiments began the

During the month preceding the offensive, the 1st Infantry Division to the south had been aggressively operating in the areas west and southwest of Hue where it cleared the approaches to FSBs Rakkasan and Bastogne in preparation for future operations towards the A Shau Valley. A major enemy buildup was evidently in progress in this area, but the division's initiatives preempted attacks against FSB Bastogne. Enemy elements positively identified were the MR Tri-Thien - Hue's 6th Regiment and the 803rd and 29th Regiments of the NVA 342B Division. Resistance by these enemy units was strong and they appeared determined to control the area around FSB Veghel, the Cu Mong Grotto and Route 547 despite the effective attacks conducted by the 1st Division.

The Initial Battles

The enemy offensive began at noon on 30 March with artillery

concentrations directed against strongpoints and firebases of the

3d Division. This fire was well planned and accurate. It was easy

for the enemy to determine the exact locations and dispositions of

ARVN troops since these positions had been used by both U.S. and

ARVN forces for many years. Additionally, the enemy's long range

130-mm field guns just north of the DMZ had the key ARVN positions

in this area well within their fields of fire. These deadly

concentrations pounded Camp Carroll, Mai Loc, Sarge, Holcomb, A4,

A2, Cl, C2 and Dong Ha Combat Base while elements of the 56th and

57th Regiments were still displacing toward their new locations,

FSBs Carroll and Charlie 1 respectively.

The unexpected assault across the D~Z caught the forward elements of the 3d Division in movement, only partially settled into defensive positions they had not been in for some time, locally outnumbered three-to-one, and out gunned by the enemy artillery. The ARVN defenses in the DMZ area were designed to counter infiltration and local attacks. There were no positions prepared to give the depth to the battlefield that would be required to contain an attack of the size and momentum of the one that had now fallen upon them.

Enemy attacks increased in intensity during the next day. All

firebases along the perimeter of the 3d Division received heavy

artillery fire. The 56th, 57th and 2d Regiments and the marine

battalions were all in contact with attacking forces. Nui Ba Ho

was evacuated late in the evening and Sarge was overrun during the

early hours of 1 April, forcing the marines to fall back to Mai

Loc. Enemy pressure forced elements of the 56th Regiment near FSB

Fuller and those of the 2d Regiment near ~e Gio to withdraw south

of the Cam Lo River. By evening of 1 April, all strongpoints along

the northern perimeter had been evacuated, including FSB Fuller and

FSB Khe Gio. The withdrawal from Al, A4, and other strongpoints,

including those manned by RF troops, was orderly and executed in

accordance with plans and consistent with the tactical situation.

However, serious mistakes were committed

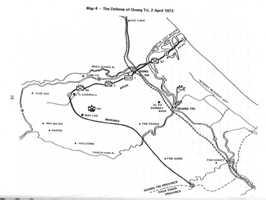

The 3d Division1s defense on 2 April appeared to be well

organized. The disposition of divisional forces was good and the

division headquarters had fairly tight control over its

subordinate units. General Giai personally supervised the

division's organization for defense and his conspicuous presence at

some forward positions restored and

The day of 2 April was marked by several tragic events. It began with simultaneous enemy attacks against Dong Ha and Camp Carroll. Again, bad weather precluded effective use of tactical air throughout most of the day. From morning to late evening, enemy tanks and infantry forces repeatedly tried to approach Dong Ha from the north. They were engaged by our 57th Regiment, the 20th Tank Squadron, the 3d Marine Battalion, U.S. Naval gunfire and were repulsed at every attempt to cross the Dong Ha bridge. The chaotic stream of refugees fleeing the combat scene along Route QL-1 since early morning deeply affected the morale of the 57th Regiment's troops who broke ranks around noon and withdrew south in disorder. If there had been a plan to evacuate civilians from the battle area, and if that plan had been well executed with suitable control and transportation, the troops of the 57th would have probably remained on position. But when they saw the disorder and panic among these refugees - among whom were their own families and relatives - the panic was contagious. When General Giai received word of what was happening, he immediately flew to the position. His presence there restored the confidence of the soldiers and they returned to their units. To stall the enemy's armor-infantry drive, the Dong Ha bridge was destroyed by ARVN engineers at 1630 hours.

Camp Carroll to the west, in the meantime, had been surrounded by

enemy troops since early morning. Troops of the 56th Regiment at

the camp valiantly endured heavy artillery fires and resisted

repeated assaults by enemy infantry but received little effective

artillery or

The loss of Camp Carroll made the defense of Mai Loc nearby extremely precarious. The 147th Marine Brigade commander decided that this base could not be held and upon his request, General Giai authorized its evacuation. The marines fell back to Quang Tri late in the afternoon. And so, repeatedly over the last three days these marine elements had been forced to withdraw and the 3d Division's AO was shrinking accordingly from both directions, the north and the west. These withdrawals had been orderly but the brigade had suffered such heavy losses during the battles of the first few days that immediately upon reaching Quang Tri it was ordered to proceed directly to Hue for regrouping and refitting. It was replaced by a fresh unit, the 369th Marine Brigade which immediately set up a new defense around FSB Nancy.

This rotation had a revitalizing effect on the marine troops in

the combat zone. It proved to be a vital factor which contributed

to the maintenance of a high level of marine combat effectiveness

throughout the enemy offensive. Unfortunately for the ARVN troops

of the 3d Infantry Division, the 1st Armor Brigade, and the ranger

groups which came as reinforcement, rotation seldom occurred.

Holding the lineAfter four days of arduous fighting and tragic setbacks, the friendly situation on the Quang Tri front remained critical. However, there were high hopes that the new defense line would stand firmly. Despite severe blows, both ARVN regular and territorial forces seemed to hold extremely well along this new line. To their credit, they had stopped the NVA invasion - for the time being. They had performed their task well, not through reliance on U.S. air support but with their own combat support. In fact, prolonged bad weather continued to preclude effective tactical air support and severely curtailed the use of helicopter gunships. But U.S. naval gunfire was helpful; so were B-52 strikes which were conducted five or six times a day against suspected NVA troop concentrations and avenues of approach. The loss of Camp Carroll and Mai Loc resulted in heavy personnel and materiel sacrifices and had an adverse psychological impact on South Vietnam, but did not seem to dampen either the morale or the self assurance of the defending forces. In the week that followed, the feeling of self assurance among ARVN troops on the firing line increased. Every attempt by the enemy to break through was thoroughly defeated. According to unit reports, several enemy attacking formations were broken up, scattered and forced to withdraw in utter disorder under the shattering fire of our infantry, armor and artillery. The enemy now withdrew to regroup and only scattered contacts and attacks by fire occurred throughout the 3d Division's area of responsibility. Although the weather continued to prevent the full use of U.S. tactical air support, the ARVN defense line held.

In the meantime three ARVN ranger groups the 1st, 4th and 5th,

arrived to reinforce the defense of Quang Tri. As the weather

showed some signs of improving, the I Corps commander gave serious

consideration to a counterattack which was to be launched as soon

as tactical air could apply its full weight. His preoccupation

with plans for a counterattack diverted the I Corps staff from

reorganizing the defense

Apparently, General Lam was overly influenced by the arrival of reinforcements. First to arrive was the 369th Marine Brigade, followed by the Ranger Command with the three groups of three battalions each, all freshly arrived from Saigon. General Lam believed that with these additional forces he could not only hold the two northern provinces but also retake the lost territory in a short time. With this conviction, General Lam repeatedly rejected the 3d Division commander's requests for reinforcement to consolidate the defense of Quang Tri. But General Giai was insistent and finally the I Corps commander reluctantly sent him first one ranger group, then another. Eventually, all four ranger groups in MR-1 were deployed to Quang Tri and attached to the 3d Division. The attachments were intended to provide General Giai with full operational control and unity of command.

However, despite its growing span of control, the 3d Division

never received additional support in logistics and signal

communications essential for the effective exercise of command and

control. This problem was recognized at the time by the I Corps

staff which recommended that the control burden placed on General

Giai should be reduced. This could have been accomplished by

placing the Marine Division under the command of I Corps, and by

giving the Marine Division and the Ranger Command each the

responsibility for a separate sector. But for reasons known only

to General Lam, these recommendations were brushed aside. Perhaps

General Lam did not feel certain he could handle the Marine

Division commander who, during LAM SON 719, had failed to comply

with his orders but still came out unscathed. As a result the

Headquarters, Ranger Command, under Colonel Tran Cong Lieu, was

left in Da Nang without a specific assignment while the Marine

Division Headquarters in Hue was not under I Corps command. This

state of things provided additional problems for the 3d Division

commander who frequently found that the orders he gave to his

attached units had no effect until the subordinate commander had

checked and received guidance from his parent

But General Lam seemed oblivious to the 3d Division commander's problems. His mood was optimistic. He believed that I Corps had enough forces to stop NVA units at the present line of defense while he and his staff were working on a plan to launch a counteroffensive. General Lam's optimism was justified by the events of 9 April. On that day, the enemy launched a second major effort, again from the north and the west. But once again, the defense succeeded in driving back all attacks. The 1st Armor Brigade, the 258th Marine Brigade and the 5th Ranger Group all reported success. Several enemy tanks were knocked out by the marines using LAW rockets and by the tank guns of the 1st Armor Brigade. FSB Pedro, which had been overrun that day was retaken the next day after 3d Division troops had repulsed three major attacks. Once more, the enemy had failed to break through the ARVN line of defense even though he had thrown into his effort major elements of the 304th and 308th NVA Divisions and two armor regiments. At the end of the day, the 3d Division 5 perimeter, which ran from the coast line along the Cua Viet River westward through Dong Ha then veered south to join FSB Pedro and the Thach Han River, was still intact. By this time, General Giai's personal responsibilities and span of control had expanded far beyond that normally expected for a division commander. As a division commander, he found himself exercising command over two infantry regiments of his own, operational control over two marine brigades, four ranger groups, one armor brigade plus all the territorial forces of Quang Tri Province. The 3d Division commander1s span of control thus included nine brigades containing a total of twenty three battalions, in addition to the territorial forces. His responsibilities also included supervising and providing protection for I Corps artillery and logistic units operating at Dong Ha, as well as monitoring the status of the provincial and district governments in Quang Tri. He was pleased and stimulated by the total trust the I Corps commander had vested in him.

Strange as it may seem, General Lam seldom felt the urge to visit

Although the counterattack plan was thoroughly discussed and considered, it was finally discarded. For one thing, the amount of forces required for success in the northward drive would greatly weaken the western flank of the defense where the enemy was stronger. If the western flank should fail to remain intact, then Quang Tri City would be in serious jeopardy. Therefore, General Lam, after considerable deliberation, decided that the counteroffensive effort should be directed westward instead of to the north. He planned to reestablish the former line of defense in the west by launching an all out attack to regain, phase line by phase line, such bases as Cam Lo, Camp Carroll and Mai Loc. At the same time, he ordered participating units to clear all enemy elements from their zones of advance before moving on to the next phase line. The counteroffensive was called Operation QUANG TRUNG 729, in an allusion to the same historical event the Communists exploited in naming their offensive. The imperial name of Nguyen Hue was Quang Trung; the operation was scheduled to begin on 14 April.

General Giai issued the orders to the 3d Division and its attached

units and QUANG TRUNG 729 began. There was no great surge of

infantry and armor crossing the line of departure, however. On the

contrary, the weary troops on the western flank were already in

close contact with

Along with the reports General Giai received from his commanders

describing their efforts to clear the enemy from their zones, came

many requests for airstrikes against enemy concentrations, strikes

that were necessary to soften the enemy before the ARVN battalions

could begin the advance to the west. As the days wore on, the

battalions in contact also flooded 3d Division headquarters with

reports of heavy enemy attacks-by-fire and high friendly

casualties. QUANG TRUNG 729 did not resemble an offensive, but

rather had settled into a costly battle of attrition in place in

which the ARVN battalions were steadily. reduced in strength and

effectiveness by the enemy's deadly artillery fire. Morale

continued to deteriorate and General Giai was unable to restore it;

neither was he able to prod his battalions out of their holes and

bunkers and into the attack. It seemed that the subordinate

commanders knew that their units lacked the strength to break

through the NVA formations facing them, that the enemy's artillery

would surely

It was during this time that the failure of I Corps to establish an effective command and control system became a serious problem. The Marine Division Headquarters and the Ranger Command, which had been sent to I Corps expressly to provide control over their organic units, continued to be left out of combat activities and received no specific assignments or responsibilities. But as parent headquarters of the marines and rangers committed to the combat zone, they contributed much to the confusion of command and control by elaborating on General Giai's orders or by questioning and commenting on everything concerning their units. They were not the only ones to do his, however. General Lam himself frequently issued directives by telephone or radio to individual brigade commanders, especially to the 1st Armor Brigade commander (who belonged to the same branch) and who rarely bothered to inform General Giai about these calls. General Giai often learned of these directives only after they had been implemented and these incidents seriously degraded his authority. Distrust and insubordination gradually set in and finally resulted in total disruption of command and control at the front line in northern MR- 1. After two weeks of continuous rain and heavy cloud cover, which seriously impeded the use of tactical air support, the weather began to improve. With an accelerated tempo as if to make up for time lost, U.S. aircraft of all types daily swarmed in the skies over Quang Tri. Air sorties by B-52's, tactical aircraft, gunships, increased steadily each day striking all suspicious targets. This upsurge restored the morale and self assurance of the ground troops.

On 18 April, enemy activity increased substantially with attacks-

by-fire and infantry-armor probes. This became the enemy's third

major effort to take Quang Tri. All ARVN and marine units reported

contact and indirect fire. At 1830 hours, a coordinated enemy

attack was launched against the western sector of the 3d Division.

From all positions, units reported movements of enemy tanks.

Within the space

The fact that another major effort by the enemy had been effectively stopped deluded the I Corps commander into thinking once more that the situation in Quang Tri was under control. But the inertia developing among ARVN units should have alerted him to the pressing requirement for reorganizing his positions and rotating weary combat units. This need totally escaped him. The enemy's demonstrated ability to conduct a sustained offensive on the other hand should also have stimulated a major ARVN effort to implement a coordinated defense plan if Quang Tri was to be held. But this effort was not made. The following week saw the defense line at Dong Ha and along the Cua Viet River cave in because of a tactical blunder. This came about when reports were received that the enemy was infiltrating from the west and threatening to cut off the supply route between Dong Ha and Quang Tri Combat Base. On his own initiative, the 1st Armor Brigade commander directed his 20th Tank Squadron on the Cua Viet line to pull back south along Route QL-l in order to clear the enemy elements there. As soon as they saw the tanks move south, ARVN troops were gripped with panic, broke ranks and streamed along. Before the 3d Division commander detected what was happening, many of his troops had already arrived at Quang Tri Combat Base and the Cua Viet defense, which was one of our strongest lines of defense from which the courageous ARVN troops had repeatedly repelled every enemy attack for nearly a month, had been abandoned. It was virtually handed to the enemy on a platter because a tactical commander had taken it upon himself to initiate a major move without reporting to his superior and without foreseeing the consequences of his actions.

Once again, by sheer physical intercession, the 3d Division

On 23 April, the 147th Marine Brigade returned to Quang Tri Base to take over its defense after a rest and refitting period in Hue. The 258th Marine Brigade redeployed to Hue but its 1st Battalion remained at FSB Pedro and came under operational control of the 147th. During the days that followed, the morale of ARVN troops deteriorated rapidly. They were exposed to the daily poundings of enemy artillery and assaults by enemy tanks. They became vulnerable to the intense tempo of conventional warfare. They had to spend long nights, tense, sleepless, agonizing at the prospect of enemy infantry assaults which could surge forward from the dark at any moment. The near total inertia of ARVN troops at night made it possible for the enemy to rest and recuperate at almost any time he chose. Therefore, short lulls during the fighting were invariably the time enemy troops chose to rest. ARVN troops in the meantime were constantly kept on the alert, under tension day and night, their energy sapped by fear and uncertainty while often defending a combat base of dubious tactical value.

Quang Tri Combat Base, north of the Thach Han River, was in fact a

bad choice for defense from a tactical point of view. As the month

of April was drawing to its end, so were the supplies at this base.

Consequently, the 3d Division commander decided then to evacuate

this base and withdraw south of the river. He worked on the

withdrawal plan by himself; he consulted only the division senior

adviser. General Giai feared that if his subordinate commanders

learned of his plan, they were apt to wreck it through hasty

actions. He also deliberately withheld this plan from the I Corps

commander. He

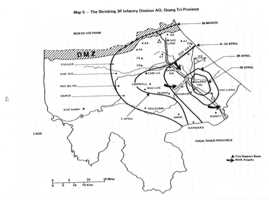

The Fall of Quang Tri City

During this time enemy attacks from the west near the boundary of Thua Thien Province cut off Route QL-l to the south and interdicted all friendly vehicular traffic over a seven kilometer stretch. This isolated I Corps forces in Quang Tri Province and completely severed the lifeline which sustained them in combat. The I Corps commander's first reaction to this situation was a series of directives to ARVN logistic units to push supply convoys through the enemy road blocks. Next, the 3d Division commander was repeatedly ordered to clear Route QL-l from the north. These orders compelled General Giai to divert an armored cavalry squadron from its vital frontline role near Quang Tri to conduct operations to the south. Finally, the I Corps commander deployed a fresh marine battalion which was committed to the defense of Hue to clear Route QL-l from the south. These movements severely exhausted fuel and ammunition supplies so critically needed in Quang Tri but were unsuccessful in reopening this vital lifeline.

The weather was particularly bad on 27 April and the enemy took

advantage of it. Actions on that day signaled the beginning of the

NVA push to capture all remaining territory held by ARVN troops in

Quang Tri Province. Along the 3d Division's new defense line,

which

The next day, 28 April, enemy tanks approached the Quang Tri Bridge, about two kilometers southwest of Quang Tri City, which was the responsibility of the 2d Regiment The armored cavalry squadron, which had been sent to reinforce the 2d Regiment was holding the bridge but it was forced to pull back. Elements of the 1st Armor Brigade also experienced setbacks during the day and had withdrawn to within one kilometer north of Quang Tri Combat Base. The brigade commander meanwhile had been wounded and evacuated. With his departure, discipline crumbled and the 1st Armor Brigade troops fled south along Route QL-l, passing through a road block set up by the 147th Marine Brigade. The 57th Regiment in the meantime had become ineffective. Its commander had no knowledge of the status of his two battalions that had been near Dong Ha City. The only troops he had with him were those of a reconnaissance platoon. Throughout the night, men continued to flow south. The only effective unit still defending Quang Tri Combat Base was the 147th Marine Brigade and it was under heavy and continuous 130-mm gun fire.

By 29 April, the situation in Quang Tri Province had become

critical. The enemy's renewed initiative pointed toward another

major effort. On their part, ARVN unit commanders at this time

were extremely concerned about fuel and ammunition shortages.

Several howitzers had already been destroyed after all available

ammunition was expended

In the face of this pending tactical disaster, on 30 April, General Giai summoned subordinate commanders to his headquarters and presented his plan to withdraw south of the Thach Han River. Basically, the plan consisted of holding Quang Tri City with a marine brigade, establishing a defense line on the southern bank of the Thach Han River with infantry and ranger troops and releasing enough tank and armored cavalry units for the pressing task of reopening Route QL-l to the south. All units were to move during the morning of the next day, 1 May. Informed of General Giai's withdrawal plan, General Lam tacitly concurred although he never confirmed his approval. Neither did he issue any directives to the 3d Division commander. In the morning of 1 May, however, General Lam called the 3d Division commander and said that he did not approve the withdrawal plan. He issued orders to General Giai to the effect that all units were to remain where they were and hold their positions "at all costs." He also made it clear to General Giai that no withdrawal of any unit would be permitted unless he personally gave the authorization. General Lam's eleventh hour countermand turned out to be a reiteration of President Thieu's directive which had just been received from Saigon. This decision was being taken presumably because the Paris peace talks had just been resumed after being boycotted by the RVN delegation since the beginning of the NVA invasion.

It was easy to pick up the telephone and countermand an order. In

the field and under heavy enemy pressure, these conflicting orders

inevitably resulted in a nightmare of confusion and chaos. General

Giai did not even have sufficient time to countermand his own

orders and at the same time impart the new orders to each of his

subordinates through a lengthy series of radio calls. Furthermore

all brigade and regimental commanders were not in a position to

carry out the new orders.

And so within the space of four hours, the ARVN dispositions for defense crumbled completely. Those units to the north manning positions around Quang Tri Combat Base streamed across the Thach Han River and continued their way south with the uncontainable force of a flood over broken dam. The mechanized elements that reached Quang Tri Bridge were unable to cross; the bridge had already been destroyed. They left behind all vehicles and equipment and forded the river toward the south. On the southern bank of the river, infantry units did not remain long in their new positions. As soon as they detected ARVN tanks withdrawing south, they deserted their positions and joined the column. But this column did not progress far. Tanks and armored vehicles began to run out of fuel and one by one they were left behind by their crews along Route QL-l. The only unit that retained full cohesiveness and control during this time was the 147th Marine Brigade which was defending Quang Tri City. Finally the brigade commander decided for himself that the situation was hopeless and he too ordered his unit to move out of Quang Tri at 1430 hours leaving behind the 3d Division commander and his skeletal staff all alone in the undefended city's old citadel. Finally, when he learned what was happening, the 3d Division commander and his staff officers boarded three armored vehicles in an effort to catch up with his own withdrawing column of troops. This occurred while U.S. helicopters came in to rescue the division's advisory personnel and their Vietnamese employees.

The 3d Division commander's attempt to join his column failed.

Route QL-l was clogged by refugees and battered troops, and all

types of vehicles, military and civilian, frantically finding their

way into Hue under the most barbarous barrages of enemy

interdiction fire.

On Route QL-l, the tidal wave of refugees intermingled with troops continued to move south. The roadway became a spectacle of incredible destruction. Burning vehicles of all types, trucks, armored vehicles, civilian buses and cars jammed the highway and forced all traffic off the road while the frightened mass of humanity was subjected to enemy artillery concentrations. By late afternoon of the next day, the carnage was over. Thousands of innocent civilians thus found tragic death on this long stretch of QL-l which later was dubbed "Terror Boulevard" by the local press. The shock and trauma of this tragedy, like the 1968 massacre in Hue, were to haunt the population of northern MR-l for a long, long time. Several ARVN units and the 147th Marine Brigade meanwhile managed to maintain some order in the midst of chaos and fought their way to the vicinity of Hai Lang. The 5th Ranger group, followed by the 1st and 4th moved on south to clear an enemy blocking unit. They were joined by the 1st Armor Brigade which took up night positions four kilometers southwest of Hai Lang. By late evening, remnants of the 3d Division found their way to the vicinity of Camp Evans where General Giai had arrived. He was attempting to reestablish his headquarters and reorganize his units.

On 2 May, the 1st Armor Brigade attempted to move south on Route

QL-l but came under heavy and continuous artillery fire. These

Armor forces finally closed on Camp Evans approximately 25

kilometers south during the early afternoon. The 147th Marine

Brigade meanwhile was also subjected to the same attack from the

direction of Hai Lang as it moved southward at dawn. With tactical

air support and the assistance of some tanks, this brigade during

the late afternoon passed

The entire province of Quang Tri was now in enemy hands. This

provided North Vietnam with the opportunity to accelerate its push

into the province of Thua Thien and toward Hue.

(1) Hue was the capital city of Central Vietnam, an ancient state whose dominions had extended from Thanh Hoa Province, now in North Vietnam, to Phan Rang; generally the coastal areas of GVN MR's 1 and 2. (2) Making a permanent shift in deployment of an ARVN division was a major undertaking, since it involved relocating thousands of families as well as soldiers and equipment. It took seven months to complete the move of the ARVN 25th Division from Quang Ngai to Hau Nghia.

|