|

THE EASTER OFFENSIVE OF 1972 by Lt. Gen. Ngo Quang Truong Published by U.S. Army Center Of Military History

Contents

Glossary

THE EASTER OFFENSIVE OF 1972

CHAPTER III

Stabilization and Counteroffensive

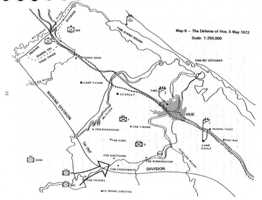

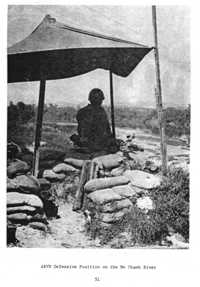

The Defense of HueDuring the month of April while the 3d ARVN Infantry Division and its attached units were battling the NVA 304th and 308th Divisions in Quang Tri Province, the 1st ARVN Infantry Division fought back several attempts by the NVA 324B Division to gain control of the western and southwestern approaches to Hue City in Thua Thien Province. Hue City was undoubtedly the prime target of enemy efforts in this area. But the seesaw battles that in fact had begun in early March then continued throughout the months of April and May without any solid gains from either side clearly indicated that this was only a secondary front designed to contain the 1st Infantry Division and support the main effort in Quang Tri.

The 1st Infantry Division and territorial forces of Thua Thien

Province acquitted themselves admirably in the performance of their

tasks. Although their exploits remained on the fringe of the

limelight which was being focused on Quang Tri and An Loc at that

time and seldom mentioned by the press, their valiance and combat

effectiveness enabled I Corps to keep the enemy in check on this

western flank and maintain overall tactical balance throughout the

most critical weeks of the enemy's Easter offensive. When this

offensive was about to enter its second week and as ARVN

reinforcements were being poured into Quang Tri Province to hold

Dong Ha and the Cua Viet line, the 1st Division was maintaining a

firm line of defense in the foothills area west of Hue. This line

extended from Camp Evans in the north, where the 1st Regiment

Headquarters was located, continued through FSB Rakkasan, then

southeast through FSBs Bastogne and Checkmate and linked up with

FSB Birmingham,

The area around FSB Bastogne and FSB Checkmate, which straddled Route 547 leading east toward Hue, was under intense enemy pressure. By the second week of April, both bases were unable to be re-supplied by road. Enemy pressure was especially heavy on the high ground northwest of Bastogne and east of Route 547 which had been interdicted. On 11 April, the 1st Regiment of the 1st ARVN Infantry Division attempted to clear Route 547 but encountered strong and determined resistance from the NVA 24th Regiment which held fast in spite of heavy ARVN artillery fire and B-52 strikes. Attempts to re-supply the beleaguered fire support bases by helicopters and air drops were only partially successful while the increasing number of wounded caused by daily enemy attacks-by-fire presented a critical medical evacuation problem. The situation around FSB Bastogne and FSB Checkmate became serious during the last two weeks of April. Enemy attacks-by-fire and ground attacks had increased considerably and all five defending battalions were down to 50 percent of combat strength. However, as the weather improved, extensive VNAF and U.S. tactical air support kept the positions from being overrun. The enemy in the meantime had brought heavy artillery to the vicinity of Route 547 and these guns presented an increased threat to Hue City.

on 28 April, elements of the 29th and 803d Regiments, NVA 324B

Division, attacked FSB Bastogne. Three hours later, they overran

this fire-base forcing a withdrawal to the east of FSB Birmingham.

Consequently, FSB Checkmate became vulnerable and was also ordered

evacuated during the night. The loss of these bases exposed Hue

City to a direct threat of enemy attack. Intelligence reports

indicated that the NVA 324B Division was being reinforced in

preparation for the push toward Hue. At the same time, there was a

significant buildup of enemy personnel and supplies in the A Shau

Valley and the 66th Regiment, NVA 304th Division, was reported

moving to the FSB Anne area, probably on its way to Thua Thien

Province.

The first days of May thus found South Vietnam's strategic posture in one of its bleakest periods during the entire war. North of Saigon, An Loc, the provincial capital of Binh Long Province, was under heavy siege. In the highlands of MR-2, the defense of Kontum City was becoming increasingly precarious. In northern MR-l, all of Quang Tri Province now lay in enemy hands; and Bastogne, the strongest bastion covering the western flank of Hue City had just caved in. Since the beginning of the offensive, the enemy's pressure in Thua Thien Province had been relatively light. But the fall of Quang Tri Province was a serious psychological blow that deeply affected the morale of troops and the local population. Confidence in the I Corps ability to defend and hold Hue was shattered and on 2 May, the exodus of panicky refugees toward Da Nang began to usher in disorder and chaos. In Hue City, throngs of dispirited troops roamed about, haggard, unruly and craving for food. Driven by their basest instincts into mischief and even crime, their presence added to the atmosphere of terror and chaos that reigned throughout the city.

It was amidst this confusion and despondency that I was ordered by

President Thieu on 3 May to take command of I Corps. I had served

in I Corps under General Lam and the disaster that occurred there

was no surprise to me. Neither General Lam nor his staff were

competent to maneuver and support large forces in heavy combat.

Now this fact was apparent to President Thieu and, because my Corps

area was

On 4 May, I immediately set about to restructure command and control. A Forward Headquarters for I Corps was established at Hue. It was staffed by senior officers who had solid military backgrounds, both in the field and in staff work, a rare assemblage of talents from all three services and service branches. I had wanted to make sure that they knew how to use sensibly and coordinate effectively all corps combat components and supporting units in a conventional warfare environment. I placed particular emphasis on developing an efficient Fire Support Coordination Center (FSCC) which was to streamline the coordinated, effective use of all U.S. and ARVN fire support. A Target Acquisition Element (TAE) was also organized to exploit the tremendous power of the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Naval gunfire.

The establishment of I Corps Forward brought about a restoration

of confidence among combat units. They all felt reassured that

from now on they would be directed, supported and cared for in a

correct manner. The U.S. First Regional Assistance Command (FRAC)

under Major General Frederic J. Kroesen and his successor, Major

General Howard H. Cooksey was most cooperative. Both gentlemen

honored me with their esteem and friendship which I highly valued.

Together we worked on outstanding problems of common interest with

a pervasive spirit of teamwork, openness and enthusiasm.

Following the implementation of this plan, I also initiated a

program called "Loi Phong" (Thunder Hurricane) which, in essence,

was a sustained offensive by fire conducted on a large scale. The

program scheduled the concentrated use of all available kinds of

firepower, artillery, tactical air, Arc Light strikes, naval

gunfire for each wave of attack and with enough intensity as to

completely destroy every worthwhile target detected, especially

those files of enemy personnel

By 7 May, our dispositions for defense in depth were well. in place. Each unit, in the forward area as well as in the intermediate echelons, knew exactly what to do. The stabilization of the battlefield had an immediate effect on Hue City. Discipline and order were restored. Stragglers were picked up, placed under control and rehabilitated. Although the fighting was still raging and the situation far from secure, the population of Hue felt reassured enough to stay in place; even those who had evacuated began to return to the city. Life in the ancient capital began to return to normalcy.

In the meantime, spirited by their recent gains, NVA forces were endeavoring to build up their combat strength and prepare for an all out drive against Hue. Probing attacks began in all sectors as our intelligence continued to report movements of enemy tanks, artillery, and anti-aircraft weapons converging on Hue. Having lost one division in the defense, I Corps required additional forces to meet the next challenge.

At my request, the Joint General Staff began to attach to my

command the airborne forces which were being re-deployed from other

battle areas in MR-2 and MR-3. The first of these, the 2d Airborne

Brigade, arrived in Hue on 8 May and was immediately deployed to

reinforce the northern sector at My Chanh, under the operational

control of the Marine Division. Soon, in keeping with the

increased tempo of enemy activities, the JGS committed another

airborne brigade, the 3d, to MR-l on 22 May. I updated my plan of

defense as soon as the Airborne Division Headquarters arrived and

was placed under my control. I assigned it, minus its 1st Brigade

but reinforced with the 4th Regiment of the 2d Division, an area of

responsibility northwest of Hue, sandwiched between the 1st

Division and the Marine Division. The division's headquarters,

under Lieutenant General Du Quoc Dong, was located at Landing Zone

(LZ) Sally. Meanwhile, the Marine Division

The rest of the month of May was a period of holding and refitting for I Corps forces. During this time, both the 1st Division and the Marine Division launched a series of limited but spectacular attacks from their forward positions. The Marine Division took the lead with a heliborne assault on 13 May during which two battalions of the 369th Brigade landed in the Hai Lang area, 10 km southeast of Quang Tri City, using helicopters of the 9th U.S. Marine Amphibious Brigade. After landing, the marines swept through their objectives and returned to their defenses at My Chanh. Caught by tactical surprise in his rear area for the first time, the enemy resisted weakly and incurred extremely heavy losses.

To compete with the marines, on 15 May, the 1st Infantry Division helilifted troops into Bastogne, caught the enemy off guard and retook the firebase while elements of its two regiments cleared the high ground south of the base and FSB Birmingham. A linkup was made the next day and ten days later. FSB Checkmate was back in friendly hands. News of the reoccupation of these key strongpoints boosted the morale of ARVN troops and deeply moved an exultant populace. Never before had the solidarity between troops and the population in MR-l been expressed with such effusion and spontaneity. The morale of I Corps troops rose to a high peak despite the lack of any organized program of motivation.

The fighting abated for about a week after the recapture of FSB

Bastogne, then resumed on 21 May when the enemy struck in force

against the marine sector in an attempt to regain the initiative.

With a concentrated armor-infantry force, supported by several

calibers of artillery, the enemy succeeded initially in breaking

through the northeast line of defense. After intense fighting that

lasted throughout the next day, the 3d and 6th Marine Battalions

finally drove back the enemy and by nightfall restored their former

positions along the My Chanh River. Even while these battles were

being fought, the Marine Division completed plans for another major

assault. In close coordination

During the same period, the Airborne Division (-) which shared in the responsibility of defending the northwestern approached to Hue, made it possible for the Marine Division and the 1st Division to become more and more aggressive. By the end of May, the 1st Airborne Brigade arrived in Hue bringing the Airborne Division up to full combat strength. And so, within the space of less than one month, the defense posture of friendly forces in MR-l had fully stabilized and became even stronger as May drew to its end. It was quite a change from the bleakest days of early May when Hue lay agonized amidst chaos, terror, and uncertainty. Now there was cause to believe that Hue would hold firm in spite of the enemy's desperate but unsuccessful efforts to break through the marines' line. On 28 May, in front of the stately Midday Gate which opened on the Old Imperial Palace at Hue, President Nguyen Van Thieu affirmed this belief when he crowned the Marine Division's successes with a new star pinned on the shoulder of its commander, Colonel Bui The Lan. General Lan solemnly vowed to take back Quang Tri City from the enemy.

Refitting and Retraining

In conjunction with the efforts to defend Hue, an accelerated

program of refitting and retraining was initiated for those ARVN

units which had suffered severe losses or had disintegrated during

the month long enemy offensive. No effort was spared to reshape

these shredded elements into combat worthy units again. This was a

high priority task

ARVN casualties and material losses were severe. Several units had deteriorated to such an extent that they needed to be rebuilt from scratch. The 1st Armor Brigade alone had 1,171 casualties and lost 43 M-48's, 66 M-41's and 103 M-113's. A total of 140 artillery pieces were either lost or destroyed; this meant that about 10 ARVN artillery battalions had been stripped of all their equipment. The 3d Infantry Division had only a skeletal headquarters staff and the remnants of its 2d and 57th Regiments. All ranger groups suffered about the same casualties which amounted to over one half of their former strength. Refitting efforts progressed rapidly and efficiently due to the dedication of ARVN logistic units under the Central Logistics Command and naturally, the quick and effective response of the U.S. logistic system under the supervision of MACV. Most equipment and material losses were quickly replaced. Among the most critical items were 105-mm howitzers, trucks and armored vehicles, individual and crew-served weapons, gas masks and other supplies such as artillery ammunition, fuses and claymore mines. All of these items were rushed to Da Nang by U.S. C-141 and C-5A aircraft or by surface ships. As a result, during this critical period no combat unit ever ran out of ammunition although the rates of expenditure had risen dramatically, especially in 105-mm and 155-mm HE.

To accelerate the retraining process, programs were shortened. A

two week quick recovery training program was conducted at each unit

by ARVN and U.S. mobile training teams, usually at battalion level

with all officers and NCOs attending. This program included both

the theory and practice of marksmanship, handling of individual and

crew-served weapons, reconnaissance and tactics. Particular

emphasis was placed on the use of anti-tank weapons, especially the

TOW missile, the first issue of which arrived on 21 May.

Initially, the training for this missile was conducted by Americans

from the 196th Infantry Brigade. Eventually, when this brigade

returned to the U.S. training was continued at the Hoa Cam Training

Center in Da Nang under ARVN instructors.

Several units, such as the 20th Tank Squadron, the 56th Regiment and the territorial forces (about 6,000 men) were required to undergo a complete refitting and retraining cycle. To facilitate control these units were assembled at two training centers, Dong Da at Phu Bai and Van Thanh on the outskirts of Hue. General Giai, who no longer had a command, was in Da Nang on 5 May when he was placed in arrest. Quite unfairly, but fully consistent with the practice in the ARVN, General Giai was held personally responsible for the defeat of his division. Although I would have been happy to have had General Giai resume command of the reconstituted 3d Division, I had no choice in the matter. I was barely able to save the name of the division, for I received many calls from the Chief of Staff, General Manh, who told me that President Thieu wanted the 3d removed from the rolls - it was "bad luck" - and to call the reconstituted division the 27th. The 3d Division, which was almost completely reconstituted immediately after the fall of Quang Tri, underwent a complete retraining program at Phu Bai. On 16 June, it relocated to Da Nang where security was more conducive to the rehabilitation process. While undergoing retraining there, it also assumed the defense of the city and an airbase complex relieving the U.S. 196th Infantry Brigade.

In general, the refitting and retraining process produced

excellent results which, in a certain sense, were comparable to

successes being achieved by our combat units defending Hue. The 3d

Division in particular recovered rapidly under the strong

leadership of its new commander, Brigadier General Nguyen Duy Hinh.

Its return to the combat scene was truly a phenomenal achievement,

according to unbiased comments by the RVN and U.S. military

authorities(2).

Quang Tri RetakenOne of the primordial tasks I Corps had to face immediately after the fall of Quang Tri was to regain the initiative. This was my primary concern when I took command. It was not an easy task, given the heavy losses, the deteriorating morale, and the precarious situation prevailing throughout the country at that time. The enemy was experiencing some problems too. His rapid success in Quang Tri, which he exploited skillfully, had advanced his forces too far ahead of his logistical capabilities. He needed time to resupply in the forward areas and meanwhile, air strikes against his supply points and lines of communications were slowing this effort. Stalling the NVA drive in MR-l was just the first step. To hold back the onrushing tide, our lines of defense had to be consolidated and our forces re-deployed and reorganized to exploit their offensive capabilities. Simultaneously and of equal importance, our troops had to be motivated by strong leadership not only to recoup their morale but also to become aggressive and imbued with an offensive spirit. This was what I began demanding from subordinate commanders, and as the situation improved, I encouraged them to plan limited offensive operations to keep the enemy off balance. These operations, which were conducted during the months of May and June with a combination of heliborne assaults and amphibious landings, were well executed and achieved excellent results. Their effect on the enemy, coupled with devastating strikes by the U.S. Air Force and Navy, was astounding. Now off balance and on the defensive, enemy forces were more concerned with their safety than the continuation of the offensive which was stalled. Our limited offensive operations had bought us enough time to prepare for the long awaited big push northward.

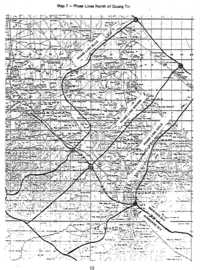

The I Corps offensive campaign, code named LAM SON 72, was

Preparations for the offensive were divided into three stages. During the first ten days of June, we repositioned forces across the front. From 11 to 18 June, the 1st Division launched an attack west in the direction of FSB Veghel while the Marine and Airborne Divisions conducted limited objective operations north of My Chanh to probe the combat strength of the enemy. From 19 to 27 June, a deception plan was initiated to confuse the enemy as to the timing and direction of the main effort. Under this plan, our forces made preparations for a fictitious airborne assault on Cam Lo and an amphibious landing on Cua Viet to cut off the enemy's supply lines and strike into his rear areas. Finally, two days before the big push, an intensive offensive by fire was to be conducted with B-52 strikes, tactical air and naval gunfire and artillery against enemy troop concentration areas, supply storages and gun positions.

LAM SON 72 was to be initiated on 28 June with a two pronged attack

northward coordinated with a supporting effort southwest of Hue.

The Airborne Division would make the main effort, attacking on the

southwest side of QL-l toward La Vang, while the Marine Division

would make the secondary effort along Route 555, moving toward

Trieu Phong. The 1st Division, meanwhile, was to pin down enemy

forces southwest of Hue. South of Hai Van Pass, in coordination

with the northward push the 3d Division was to continue ensuring

the defense of Da Nang by conducting economy-of-force operations

concurrent with its training and refitting program. In the

meantime, the 2d ARVN Division was to conduct search

The plan was submitted simultaneously to Saigon by I Corps Headquarters and FRAC about two weeks before D-day. A day or so later, General Cooksey my senior adviser, told me that MACV had reviewed my plan and suggested that it would be better if I would continue limited spoiling attacks and consider a counteroffensive at a later date. This disturbed me greatly, for my troops were eager to go. I was ready, and it was a good, carefully worked out plan. I decided to present it personally to the President, feeling confident that he would support it. He needed a victory in MR-l to strengthen his political support. I flew to Saigon and explained the plan in detail to the President, the Prime Minister, General Quang (the Presidentts national security deputy) and General Vien. President Thieu listened, then, taking a purple grease pencil, drew an arrow on my map, suggesting a spoiling attack. The Prime Minister agreed, commenting on the French attack on the "street without joy." Discouraged, I folded my map and flew back to Hue. I worried about this all night and very early the following morning called General Quang and told him that I would present no more plans to Saigon. If they wanted me to do anything, they should give me a Vietnamese translation of whatever plan they wanted me to execute and I would comply. The President called me about 0900 and told me that he was concerned about my plan - that he fe1t it was too ambitious - but that he would like me to return to Saigon and show it to him again. This I did the next day and, after a brief discussion, the President approved the plan.

LAM SON 72 began on 28 June as planned. Both the airborne and

marine spearheads made good progress but slower than we expected.

Enemy resistance was moderate during the first few days except for

a few regimentaln size clashes that occurred when our forces crossed

the enemy 5 first line of defense north of the My Chanh River.

However, as the enemy fell back and our forces advanced near the

Thach Han River, his resistance became heavier.

By this time, the enemy's determination was all too clear; he planned to hold Quang Tri City to the last man. The enemy's ferocious resistance was such that Quang Tri City suddenly became a "cause celebre" that attracted emotionally charged comments by public opinion throughout South Vietnam. Although it had not been a primary objective, it had become a symbol and a major challenge. The enemy continued reinforcing; he was determined to go all out for the defense of this city. The ARVN drive was completely stalled. I Corps' position at this juncture was a difficult one. Pushed by public opinion on one side and faced with the enemy's determination on the other, it was hard pressed to seek a satisfactory way out. My final assessment was that we could not withdraw again from Quang Tri without admitting total defeat; our only course was to recapture the city. Therefore, I directed a switchover of zones and assigned the primary effort to the Marine Division. The offensive then took on a new concept but the mission remained the same. I concluded that if the enemy indeed chose to defend Quang Tri City and concentrated his combat forces there, he would give me the opportunity to accomplish my mission employing the superior firepower of our American ally.

Because of the enemy's determined defense, the recapture of Quang Tri City became a long, strenuous effort which carried into September. By that time, total enemy forces in Quang Tri and Thua Thien Provinces alone reached the incredible proportions of six infantry divisions, the 304th, 308th, 324B, 325th, 320B and 312th. The 312th Division had been re-deployed from Laos and introduced into Quang Tri along with troop reinforcements for the other divisions. The showdown was inevitable. But the balance of forces was lopsided; the enemy had more than enough strength to contain South Vietnam's three divisions, even though they were our best ones. In spite of continuous, violent clashes and the enemy's ferocious artillery fire which averaged thousands of rounds daily, I Corps forces were able to keep the offensive momentum going. This was possible because we rotated the frontline units, giving them a chance to rest and refit. The balance of forces, however, still favored the enemy heavily, which at times raised the question of whether we should reinforce MR-l with additional troops. Consideration was even given to deploying an infantry division from MR-4, but the idea was finally rejected as neither feasible nor absolutely necessary. The military situation throughout South Vietnam during that critical period was such that the redeployment of a major unit would have seriously weakened the losing military region.

But neither the enemy's opposition nor the protraction of the

campaign seemed to affect I Corp's tactical posture and

determination. I believed that it was just a matter of time because

all the ingredients for our success were there: a firmly

established command and control system, a dedicated staff, and

adequate support. The drawn out contest between our forces and the

enemy for this coveted objective might even be advantageous to us;

if we had succeeded in retaking Quang Tri during the very first few

days of the campaign, the battle area would

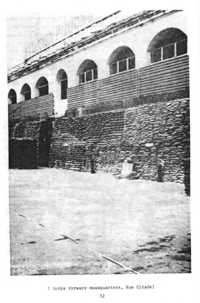

When the offensive campaign entered its tenth week in early September without a decisive outcome in sight, I decided that the delay had been long enough. Enemy forces by that time had been reduced considerably by the volume of firepower delivered by B- 52's, tactical air, artillery and naval gunfire; I was personally convinced that a new major effort by I Corps stood a good chance for success. A victory at this juncture would not only reinforce the RVNVS military posture - the enemy had been defeated at An Loc and Kontum - it could also bring about excellent returns in a political sense. On 8 September, therefore, I Corps launched three separate operations to support its major objective, retaking Quang Tri City. The Airborne Division advanced and reoccupied three key military installations formerly under ARVN control at La Vang, south of the Quang Tri Old Citadel. From these positions, the paratroopers were able to provide excellent protection for the southern flank of the marines. The next day, the Marine Division initiated the main effort, attacking the Old Citadel. At the same time, U.S. and RVN forces conducted an "incomplete" amphibious assault on a beach north of the Cua Viet River; the purpose was diversionary. At first, the enemy1s determined resistance slowed the marines1 progress, but elements of the 6th Marine Battalion penetrated one side of the citadel's walls on 14 September. During the following day, more marines were injected into the breach and other marine spearheads repeatedly assaulted the eastern and southern faces of the citadel. During the night of 15 September, the marines regained control of the citadel. Finally, in the morning of 16 September, the RVN flag was raised on the citadel amidst the cheers of our troops. This was a day of exalting joy for the entire people of South Vietnam.

By late afternoon of the next day, the marines had eliminated the

After Quang Tri City was retaken, the level of enemy activities throughout northern MR-1 dropped off markedly, especially in the marines' sector. This low activity level continued until 30 September when the Airborne Division again launched attacks to reoccupy FSB 3arbara and FSB Anne. The paratroopers' attacks met with fierce enemy resistance Their progress was slowed not only by heavy enemy artillery barrages but also by drenching monsoon rains. As October drew to its end, however, the Airborne Division finally reoccupied FSB Barbara and shifted its effort toward FSB Anne to the north.

In the meantime, the 1st Infantry Division sustained its initiative in Thua Thien Province. In addition to defending Hue, the division had the mission to conduct offensive operations to extend its area of control to the west and southwest. Activities in the 1st Division's sector were moderate during early June. They were mostly concentrated on the areas of FSB's Birmingham, Bastogne and Checkmate and along Route 547. By the end of June, however, enemy pressure bacame heavier.

During July, FSB Checkmate was subjected to heavy enemy attacks

during which it was overrun and retaken several times. Toward the

end of the month, FSB Bastogne also came under enemy control. For

the first time in five months of hard fighting and under constant

pressure, the 1st Division began to show some signs of weariness.

Still, it held on to and maintained its line of defense. To help

the division regain its vitality and aggressiveness, I decided to

reinforce it with the 51st Regiment. Then, in early August, with

the strong support of B-52 strikes and U.S. tactical air, the

division successively retook Bastogne and Checkmate. During this

month, as the enemy gradually lost his initiative, the 1st Division

began to launch attacks to enlarge its control toward the west.

Taking advantage of its renewed determination, the division even

took back Veghel, the remotest fire support base to

From the time I Corps began offensive operations in Quang Tri Province to the end of July, the three provinces south of the Hai Van Pass were able to maintain reasonable control despite the low strength of friendly forces. Although sparsely used, B-52 strikes continued to be directed against a number of selected targets. However, as friendly forces in northern MR-l approached Quang Tri City and were concentrating their efforts on this objective, the enemy suddenly chose to initiate several heavy attacks, especially in the area of the Que Son Valley, against elements of the 2d ARVN Infantry Division. This move was in all probability intended to alleviate our pressure on Quang Tri. Da Nang Air Base was also heavily rocketed many times. Enemy pressure was particularly strong on remote district towns in the foothills areas. Some of them were overrun after protracted sieges. In the face of the enemy's mounting pressure, the 2d Infantry Division, now under Brigadier General Tran Van Nhut, was directed to concentrate its effort on the southernmost province, Quang Ngai, where the threat posed by the NVA 2d Division was increasing. Meanwhile, the 3d Infantry Division was assigned the mission to clear the pressure that the NVA 711th Division was exerting in the Que Son Valley and also to retake the district town of Tien Phuoc in Quang Tin Province. Despite superior enemy forces, both ARVN divisions were determined to fulfill their missions and performed extremely well. The successful operation conducted by the 3d Division to retake the district town of Tien Phuoc in particular - its first major engagement since its battered withdrawal from Quang Tri not long ago - truly marked its regained stature and restored to some extent the popular confidence vested in it.

Toward the end of October, the overall situation in MR-l was completely stabilized. As the possibility for a negotiated cease- fire increased with every passing day, the people of Quang Tri, Thua Thien

Role of U.S. Air and Naval SupportDuring the entire period of the enemy's Nguyen Hue offensive campaign in MR-l, the support provided by the Vietnamese Air Force and Navy was marginal although they were employed to the maximum of their limited capabilities. Therefore, when the fighting broke out with great intensity and such a large scale, ARVN units had to rely mostly on support from U.S. Air Force and Naval units. This support was effective and met all of I Corps requirements. Before April 1972, U.S. air activities in MR-l were at a low level. Any 24-hour period with more than 10 tactical air sorties was considered a busy day. When the enemy1 5 offensive began, however, U.S. air sorties increased dramatically. At one time, these sorties numbered 300 or more per day. Despite almost continuously bad weather during the month of April, air support was substantial and contributed initially to slowing down the advance of enemy forces and eventually stalling it altogether. B-52 strikes also increased remarkably during this period, averaging in excess of 30 missions a day. These strikes caused the most damage and greatest losses to enemy support activities. They were also used to provide close support to ARVN ground forces on several occasions. In addition to support provided the U.S. Air Force, I Corps forces also received much assistance from the U.S. Army 11th Combat Aviation Group whose activities were closely coordinated with those of ARVN units. This group provided essential support with troop lift logistical support and gunships. During the early days of the enemy's invasion of Quang Tri, U.S. Air Force fire support missions were not only impeded by inclement

The NVA air defense effort increased during their invasion. At first SAM sites were located in the DMZ area along with antiaircraft guns but as NVA forces advanced south, they were also displaced south to the vicinity of Cam Lo and Route QL-9. Coverage by these missiles and guns thus extended to include our My Chanh line of defense. Throughout this forward battle area, enemy antiaircraft machineguns, artillery and SA-2 missiles were deployed in a dense pattern. During May, coordination procedures for the use of air support were vastly improved after the relocation of I Corps Air Operations Center to Hue where it was co-located and operated in conjunction with the Fire Support Coordination Center. This provided much better coordination and timely control. In addition, tactical air control parties (TACP) were also deployed to operate alongside division tactical command posts. This newly arranged system of coordination and control, added to I Corps' gradual restoration of tactical initiative, greatly expanded the use of air support which totaled in excess of 6,000 sorties for the month. Enemy positions and artillery emplacements, particularly 130-mm guns, suffered severe losses; most spectacular were the results achieved through the use of laser-guided bombs and the technique of radar-guided bombing using aerial photo coordinates.

As to naval gunfire, its support was modest during the first day

of the enemy invasion since only two destroyers, the USS Straus and

USS Buchanan, were operating offshore MR-l during late March. When

the offensive broke out, however, all naval gunfire ships in the

vicinity were immediately dispatched to the area and began

providing support for the beleaguered 3d Division units. The level

of naval gunfire support increased with every passing day. At one

time during the month of June,

Naval gunfire was particularly beneficial to the Marine Division. With its all weather capabilities, naval gunfire responded perfectly to every support requirement within its range. During the period of I Corps stabilization and counteroffensive, the number of ships available for support varied from eight to 41 and the number of rounds fired ranged from a high of 7,000 to a low of 1,000 daily. For the control of fire, forward observer teams were attached to I Corps major units such as the infantry divisions, the 1st Ranger Group, and the Marine and Airborne Divisions and to the sectors of Quang Tin and Quang Ngai in southern NR-l.

In general, fire support available from U.S. and RVN sources was

plentiful for I Corps throughout the enemy offensive. But the

judicious and timely use of it proved to be a difficult problem in

coordination and control The establishment of a fire support

center at Hue in May 1972 was a step in the right direction. For

the first time, it enabled I Corps to integrate and make the most

effective use of all U.S. and RVN fire support available. Because

of its smooth operation, the center contributed significantly to

the ultimate success of I Corps. It could be regarded as the

symbol of effective cooperation and coordination, not only between

U.S. and RVN elements, but also among our various services and

service branches.

(1) The division's former commander, Lieutenant General Le Nguyen Khang, was offered the command of II Corps by President Thieu but he declined. He was later appointed Assistant Chief of the JGS for Operations.) (2) On1y a year later, in 1973, the 3d Infantry Division was rated by the Joint General Staff as the best among ARVN divisions. Its commander was also the only division commander to be promoted to the rank of Major General during the year.

|