|

THE EASTER OFFENSIVE OF 1972 by Lt. Gen. Ngo Quang Truong Published by U.S. Army Center Of Military History

Contents

Glossary

THE EASTER OFFENSIVE OF 1972

CHAPTER V

The Siege of An Loc

The Enemy's Offensive Plan in MR-3When the NVA crossed the DMZ and invaded Quang Tri Province on 30 March, the Joint General Staff was still having serious doubts about the enemy's real objective. Hue was apparently an immediate target. It had always been one of prime importance because of its historic stature. But evidence of enemy buildup in Kontum Province also presaged something serious in that area. The long held theory that the enemy might attempt an attack across the Central Highlands to the sea to split South Vietnam into two parts was still in the minds of many Vietnamese and American strategists. If so, the Kontum Plateau could become another target of great strategic significance. Little attention was being devoted to Military Region 3, however, although there was always the possibility of enemy offensive against Tay Ninh Province and perhaps Saigon itself. The enemy's disposition and capabilities along the entire western flank of South Vietnam, with his easy access to and from sanctuaries in neighboring Laos and Cambodia, made the problem of deducing the enemy's main effort all the more difficult. His advantage was such that the initial success of any thrust could quickly be reinforced and turned into the main effort; if not, it would serve some tactical purpose in support of other attacks. This flexibility was most likely what he had in mind when the southern arm of his Easter invasion struck Loc Ninh on 2 April.

Because of its proximity to Saigon by way of Route QL-13, the

attack on Loc Ninh naturally raised the question of the enemy's

ultimate objective. Was it Saigon, the capital, where all RVN

military and political decisions were made?

Eleven provinces surrounded Saigon; among them Bien Hoa was by far the most important, being an industrial area and the site of III Corps Headquarters. Bien Hoa also contained a large Air Force base and the headquarters of the U.S. Army, Vietnam and the U.S. II Field Forces, both of which were located in the Long Binh base complex. The second most important province of MR-3 was Tay Ninh - the holy land of the influential Cao Dai sect - whose northwestern corner was a well known enemy base area, Duong Minh Chau (War Zone C) which was the home and haven of enemy military and political leaders. The field forces of III Corps consisted of three ARVN infantry divisions, the 5th, 18th and 25th and three ranger groups, the 3d, 5th and 6th. The 25th Division was assigned an area of operation encompassing the provinces of Tay Ninh, Hau Nghia and Long An, but the division headquarters and its three subordinate infantry regiments were usually located and operated in Tay Ninh Province. The 5th Division was responsible for the area of operation covering Phuoc Long, Binh Long and Binh Duong Provinces. Its headquarters was located at Lai Khe in Binh Duong Province. The 18th Division's area of operation extended over the provinces of Bien Hoa, Long Khanh, Phuoc Tuy and Binh Tuy. It was headquartered at Xuan Loc, the provincial capital of Long Khanh.

During the period from January to March 1972, ARVN intelligence reported the presence of the NVA 5th Division in Base Area 712, near the Cambodian town of Snoul, about 30 kilometers northwest of Loc Ninh on Route QL-13. The other two enemy divisions, the 7th and 9th, were located in the Cambodian rubber plantation areas of Dambe and Chup, which were two of III Corps's operational objectives planned for the third quarter of 1971, plans which were suspended after the accidental death of Lieutenant General Do Cao Tri, III Corps commander General Tri's successor, Lieutenant Nguyen Van Minh, advocated a strategy of standoff defense at the border instead of deep incursions into enemy base areas in Cambodia. During this period, the ARVN commanders of III and IV Corps had independent authority to conduct operations deep into Cambodia, so long as they coordinated with their counterpart military region commanders in the Cambodian Army. They, of course, informed Saigon of their plans, but Saigon exercised practically no influence on the strategy each Corps commander decided to adopt.

All three enemy divisions were undergoing refitting and political

indoctrination during the first quarter of calendar year 1972 but

in late March we received the first information concerning a

movement of the 9th NVA Division. It was provided by an enemy

document captured during an operation in Tay Ninh Province

(1). According to the document,

The training of enemy troops for urban warfare was most significant because this training had been discontinued since 1969 in the aftermath of the Tet offensive. Not until late 1971 was this type of training known to be resumed for a few enemy main force units. Therefore, this document which revealed that the 9th Division had completed urban warfare training was especially important in planning the defense for III Corps.

In spite of these revealing pieces of information, III Corps

Headquarters still did not focus adequate attention on Binh Long,

In some aspects, III Corps Headquarters was right in depreciating Binh Long as a major objective; for one thing, Binh Long was much farther from the enemy's border base areas than Tay Ninh. Demographically, it was insignificant compared to Tay Ninh (60,000 versus 300,000 inhabitants). In brief, compared to Tay Ninh, Binh Long lacked all the conditions required to be a major enemy target except for two things. First, offensive operations in Binh Long could be supported from base areas in Cambodia as well as from those inside MR-3. Second, ARVN defenses in the province were weak.

The enemy's offensive in MR-3 began in the early morning of 2

April when his 24th Regiment (Separate) with the support of tanks,

attacked Fire Support Base Lac Long located near the Cambodian

border 35 kilometers northwest of Tay Ninh City. This base was

defended by one battalion of the 49th Regiment, 25th Division. The

enemy's commitment of tanks contributed to the rapid collapse of

this base which was overrun by midday.

Scattered contacts with the enemy were made by all border outpost elements as they withdrew toward Tay Ninh City. The defenders of FSB Thien Ngon, approximately 35 kilometers north of the city, were ambushed by the 271st Regiment (Separate) and suffered heavy losses in vehicles and weapons, especially 105-mm and 155-mm howitzers. When reinforcements of the 25th Division arrived at the ambush site the next day, they were surprised to find that all abandoned vehicles and artillery pieces were still there, untouched by the enemy. Strangely, the attacking unit had moved away instead of pressing toward Tay Ninh City. This riddle was finally solved much later when a prisoner from the 271st Regiment disclosed that the attack on the Thien Ngon defenders had been only a diversion to detract III Corps from the main NVA effort being directed toward Binh Long Province with Loc Ninh as the first objective.

Although the details of the enemy's plan did not become known

until after the battle was joined in Binh Long and battlefield

intelligence information began to accumulate, filling in the gaps,

COSVN would commit three divisions and two separate regiments, all

with armor reinforcements to the Binh Long campaign. The first

phase was the

The Attack on Loc NinhThe attack on Loc Ninh began with an ambush on Route QL-13, five kilometers north of the town on 4 April. Ordered to fall back from the border to reinforce the defense of Loc Ninh, an ARVN armored cavalry squadron (-) attached to the 9th Regiment of the ARVN 5th Division was ambushed by an infantry regiment of the NVA 5th Division. Very few ARVN survivors managed to reach the district town. Early the next morning, the district defense forces reported hearing enemy armor on the move. A few hours later, the enemy began to shell heavily then attacked the Loc Ninh subsector headquarters and the rear base of the ARVN 9th Regiment located in the town. The defenders resisted fiercely and employed the effective support of U.S. tactical air which was directed onto enemy targets by the U.S. district advisers. By late afternoon, the enemy's attempt to capture the Loc Ninh airstrip was defeated by CBU bombs of the air force. During the early hours of the next morning, 6 April, the enemy attacked again, this time with the addition of an armor battalion estimated at between 25 and 30 tanks. Despite direct fire by ARVN artillery to stop the advancing tanks, Loc Ninh was overrun a few hours later. A number of survivors managed to break through and made it to An Loc; on 11 April, An Loc received the first group of 50 ARVN solders. The next day, they were joined by the Loc Ninh district chief who was soon to be followed by his senior adviser.

While Loc Ninh was under attack, the ARVN 5th Division ordered the

By this time, Loc Ninh had been overrun. The 52d Task Force was ordered to fall back by road to An Loc to reinforce its defenses, but it was intercepted and attacked at the same road junction. After incurring heavy losses the 52d Task Force withdrew into the jungle and by using alternate routes finally reached An Loc. Although disorganized and battered, the task force contributed additional personnel critically needed at that time for the defense.

The Siege and First AttacksOnly after the enemy's attack on Loc Ninh had been initiated was the III Corps commander, General Minh, fully convinced that An Loc City would be the primary objective of the enemy offensive. He also realized that if An Loc were overrun, Saigon would be threatened because only two major obstacles would remain on Route QL-13 north of Chon Thanh and Lai Khe. Therefore, An Loc was to be reinforced at once and held at all costs. General Minh acted rapidly. The 5th Division Headquarters, with Brigadier General Le Van Hung in command, and two battalions of the 3d Ranger Group were helilifted into An Loc. This movement was completed without difficulties on 5 April, but by this time, III Corps no longer had a reserve.

During a meeting on 6 April at the Independence Palace in Saigon

to review the military situation throughout the country, General

Minh pleaded his case for more troops for the defense of An Loc.

His request was overruled by considerations given to the

seriousness of

At this meeting, attended by all corps commanders, Generals Quang and Vien, as well as the president and prime minister, the requirements of each corps for reinforcements were discussed. When it was suggested that the 21st Division be deployed to reinforce I Corps, General Quang argued that the situation at An Loc was potentially even more serious than the problem in Quang Tri. If the NVA succeeded in establishing a PRG capital at An Loc, the psychological and political damage would be intolerable for the GVN. The president agreed and the subject of which IV Corps division would reinforce III Corps was discussed. Consideration was first given to using the 9th Division, but as IV Corps commander at the time, I suggested the 21st Division, for two reasons(3). First, the 21st Division was conducting successful search and destroy operations in the U Minh Forest and it was particularly effective in mobile operations. Second, the 21st Division had once been commanded by General Minh; placing it under his control again would not only facilitate employment and control by III Corps but also bring out the best performance from the division.

On 7 April, the 1st Airborne Brigade was ordered to move by road

from Lai Khe to Chon Thanh. From there, it was to conduct

operations northward to clear Route QL-13 up to An Loc and keep

this vital supply line open. When reaching a point only six

kilometers north of Chon Thanh, still 15 kilometers short of An

Loc, the brigade's advance was

After taking Loc Ninh, the NVA 5th Division began moving south toward An Loc. Beginning on 7 April, the local population living in the vicinity and workers in rubber plantations nearby reported the presence of NVA regular troops. Very rapidly, all food items in local markets around An Loc, especially canned or dried food began to disappear from display counters. Intelligence reports indicated that the enemy's rear services had preempted these food items to keep the combat units supplied while moving toward the next battlefield. The city itself was not yet under attack but the Quan Loi airstrip, three kilometers east, came under fire and infantry assaults during the evening of 7 April. The fierceness of this attack was such that two ARVN companies which defended the airstrip were ordered to destroy their two 105-mm howitzers and fall back to the city. Two days later they arrived at the edge of An Loc. The loss of the Ouan Loi airfield edged An Loc into complete isolation because both air and ground communication with the city had now been cut off. The high ground in the Quan Loi area which dominated the city from the east also offered the enemy good artillery emplacements and observation from which he could pound targets in the city with deadly accuracy. Despite this, the 9th NVA Division did not attack the city until several days later. The reason for this delay, as later learned from enemy prisoners, was that logistic preparations had not been completed to support for the attack. According to COSVN's planning, it should take about one week to destroy all border outposts and during this time, supplies were to be moved forward for the attack on An Loc. The sudden evacuation of border outposts by the III Corps commander had thrown the enemy's plan into disarray and the 9th Division was forced to delay its attack after it had moved into position.

By 7 April, An Loc was entirely encircled and without a fixed wing

airstrip. Between 7 and 12 April all supply missions were flown by

VNAF helicopters and C-123's. The use of helicopters ended on the

12th when a VNAF CH47 was shot down by antiaircraft fire. From

then until

In the meantime, reinforced by the 21st ARVN Division under the command of Major General Nguyen Vinh Nghi, III Corps was able to deploy the 8th Regiment, 5th ARVN Division with its two battalions to augment the defense of An Loc. Movement of this 8th Regiment was completed during 11 and 12 April, all by helicopter. The defending force in the city by this time numbered nearly 3,000 men, including RF and PF troops. Chinook" CH-47 helicopters were used extensively to move in more supplies and evacuate the wounded and refugees.

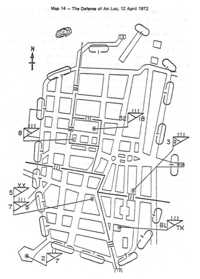

During the early hours of 13 April, the enemy began to shell the city heavily. Then shortly after daylight, units manning positions northwest of the city reported several enemy tanks and vehicles moving toward the city. An AC-130 Spectre gunship on station engaged the enemy and destroyed one tank and four vehicles. Simultaneously, several other tanks were reported on the northern side of the perimeter. By 0600 hours, the first major attack had begun against positions held by the 7th Regiment on the west. The main effort seemed to be developing from the north, however, spearheaded by armored vehicles. Overwhelmed by superior enemy forces, the ARVN defenders on this side quickly fell back.

A remarkable highlight during the first few hours of fighting was

the effective use of the M-72 LAW rocket. In fact, the first tank

killed by the ARVN defenders during the enemy attack on An Loc was

scored by a RF soldier. Word of this feat spread rapidly among

ARVN troops and their confidence was greatly enhanced. It was as

if in just a matter of minutes, the long established fear of enemy

tanks had

By this time, several enemy tanks had breached the defense and penetrated well into the city, but they remained isolated and no accompanying enemy infantry was in sight. One T-54 tank in particular rolled aimlessly through the city from north to south before it was destroyed by M-72 fire. Finally, four enemy tanks were knocked out and another one surrendered after its crew ran out of ammunition. Taken prisoner, one of the crew members declared he belonged to the 1st Battalion, 203d NVA Tank Regiment. His unit had moved from North Vietnam through lower Laos and then took shelter in Cambodia. His unit was ordered only the day before to move into Binh Long Province from the border and participate in the An Loc battle. The III Corps commander appeared to be surprised by the presence of enemy tanks in Binh Long. He seemed to blame ARVN intelligence unduly for that surprise. However, in fact, as early as October 1971, ARVN intelligence reports had indicated the presence of enemy armor in the areas of Kratie, Dambe and Chup on Cambodia territory. In December 1971, the G-2 Division of the National Khmer Armed Forces General Staff also confirmed the existence of approximately 30 NVA tanks in Base Area 361, based on local informant sources. However, air photo missions had failed to record any traces of enemy armor movements probably since these movements were conducted at night. As a result, these ARVN and Khmer intelligence reports might not have convinced our III Corps commander. The enemy probably considered the commitment of his tanks in MR-3 to be the key to success. He was certain that he could take Binh Long in five or ten days, and in any event no longer than ten days. To ensure success and because neither the 9th NVA Division nor its regimental or unit commanders had any experience with combined arms tactics, COSVN decided that COSVN Military Command would directly control the tank units. The results were disastrous. It was obvious that enemy tanks had led the attack and penetrated the perimeter without any support or protection from infantry units.

During 13 April, both the 271st and 272d Regiments of the 9th NVA

After two days of fighting, the morale of the defenders remained remarkably high. They all seemed pervaded by the spirit of "holding or dying", determined to keep An Loc in friendly hands. This came from their conviction that they would never be left to fight alone and that they would be kept well supplied and reinforced as required. Their convictions were right throughout the battle for An Loc. The 1st Airborne Brigade meanwhile had been withdrawn from the Tau O area, quickly refitted, and helilifted during 13 and 14 April into positions on Hill 169 and Windy Hill, three kilometers southeast of An Loc. The presence of paratroopers in the vicinity of the isolated city greatly encouraged the ARVN defenders and local population. Their confidence received an additional boost when they learned that the 21st Infantry Division from the Mekong Delta had reached Tau O on its way northward to relieve An Loc. So when the enemy resumed his attacks on 15 April with the support of 11 tanks, these tanks became targets for ARVN troops competing among themselves for quick kills. One of these tanks managed to reach a position where it fired point blank at the 5th Division tactical operations center, wounding the S-3 of Binh Long Sector and two other staff officers. When the dust of the battle cleared at day's end, 9 of the 11 tanks committed by the enemy had been destroyed.

The battle of An Loc abated somewhat on 16 April. After three

days of combat, the enemy had lost 23 tanks, most of them T-54's

and T-59's. However, the northern half of the city remained in his

hands

The first enemy effort to take An Loc resulted in failure and COSVN modified its plan for the next effort. It decided to support the next major attack with a secondary attack against the ARVN 1st Airborne Brigade on Hill 169 and Windy Hill southeast of the city. This secondary effort would be conducted by two regiments, the 275th of the 5th Division and the 141st of the 7th Division. The main attack on An Loc would remain the 9th Division's responsibility. To minimize the effectiveness of our tactical air, the enemy also ringed the city with additional antiaircraft weapons. The enemy's new plan of attack, however, came into our possession on 18 April. On that day, in an ambush laid on an enemy line of communication near Tong La Chan Base, ARVN rangers killed an enemy and found on his body a handwritten report from the 9th NVA Division's political commissar addressed to COSVN Headquarters. This report analyzed the initial failure of the 9th NVA Division and attributed it to two major reasons. First, the intervention of U.S. tactical air and B-52's had been devastating and most effective. Second, coordination was ineffective between armor and infantry forces. The report also contained plans for the new major attack on An Loc which was to begin on 19 April. With this new plan, the enemy apparently believed An Loc could be seized within a matter of hours. So confident was he of success that on 18 April, a Hanoi Radio broadcast announced that An Loc had been liberated and that the PRG would be inaugurated in this city on 20 April.

In the early morning hours on 19 April, the enemy's attack

proceeded exactly as planned and outlined in the captured document.

While An Loc City came under heavy artillery and rocket fire, the

NVA 275th and 141st Regiments attacked the ARVN 1st Airborne

Brigade on Hill 169 and Windy Hill with the support of six tanks.

This attack was so vigorous that the brigade headquarters on Hill

169 was overwhelmed and the 6th Airborne Battalion was forced to

destroy its 105-mm battery and withdraw. Two companies of this

battalion and the 1st Airborne Brigade Headquarters

Meanwhile the 9th NVA Divison's attack on the city itself again ended in failure. Its troops were unable to advance in the face of the determined ARVN defenders who still firmly held the southern half of the city. The enemy then modified his plan of attack, attempting to move southwest to Route QL-13 and attack An Loc from the south. This plan never materialized for the enemy discovered that on 21 April, his staging area, a rubber plantation just south of the city had been occupied by two battalions of the 1st Airborne Brigade who were firmly entrenched there. Unable to carry out the new plan, the enemy slackened his pace of attack which finally came to a halt on 23 April, ending in failure his second attempt to take An Loc. Within the besieged city, friendly forces did not fare much better than the enemy, however. The northern half of the city remained in enemy hands. The enemy's defense in the northeastern quarter was particularly strong and unbreachable. The city's southern half meanwhile came under increasingly heavy attacks-by-fire everyday. On 25 April, the city's hospital was hit and destroyed. As a result, no medical treatment was available for our wounded, military and civilian alike. All casualties had to be treated in the areas where they were wounded. Medical evacuation in the meantime became impossible because of intense antiaircraft fire. The city was littered with bodies, most of them unattended for several days. To avoid a possible epidemic, our troops were forced to bury these bodies in common graves. Supplies were running low; most critically needed were food, ammunition and medicine. Keeping the city re-supplied was becoming increasingly difficult. Because of heavy enemy antiaircraft fire, our helicopters only occasionally succeeded in reaching the city and then only for emergency re-supply missions.

Beginning on 20 April, all re-supply missions were conducted by

The initial method used by the C-130's for airdrops was the HALO (High Altitude, Low Opening) technique. In this technique, the supply bundles were dropped from a safe altitude of 6,000 to 9,000 feet, and parachutes opened only at 500-800 feet above the drop zone. In the first eight HALO missions, most bundles fell outside the stadium and into enemy hands. This failure was traced to improper parachute packing by ARVN aerial re-supply personnel who obviously lacked the technical training and experience required for the HALO method. Since this problem could not be solved immediately, the USAF reverted temporarily to the low altitude container delivery method requiring daylight drops. But the C-130's were particularly vulnerable at low speeds over the drop zone and although they succeeded in delivering supplies to the ARVN defenders, the enemy's well placed antiaircraft fire caused considerable damage to almost every aircraft. These low altitude daylight missions were cancelled again on 26 April when one aircraft took a direct hit and exploded. Now it appeared that delivery at night was the only alternative pending a satisfactory solution to the HALO system. But night delivery had its own drawbacks in that the drop zone was difficult to identify in darkness even with marker lights. Various techniques were tried to improve delivery but did not provide desired results. The delivery rate therefore declined considerably and after a third crash, all re-supply drops were discontinued on 4 May. In the meantime, at the request of the Central Logistics Command, U.S. Army logisticians and USAF technicians had been working feverishly to solve the problem of parachute malfunctions. Two teams of qualified packers arrived from Okinawa to assist in packing and training ARVN personnel. Immediately, results improved Two methods were tested on 4 May, HALO and High Velocity. Both proved remarkably accurate and as a result, aerial deliveries kept An Loc adequately re-supplied until the day the siege was lifted.

During this time, our General Political Warfare Department had

been especially active in enlisting popular support for the ARVN

While re-supply from the air proceeded without crippling problems, the recovery and distribution of supplies on the ground remained very difficult. Without coordination and control, it was usually those units nearest to the drop zone that got the most supplies. To solve this problem, the 5th Division commander placed Colonel Le Quang Luong, the tough 1st Airborne Brigade commander, in charge of recovery and distribution of airdrops. Another difficulty which occurred during the recovery of airdrops was the problem of enemy artillery fire which was placed on the drop zone. As soon as a supply drop was made, the enemy immediately concentrated his fire on the stadium area. Consequently, very few soldiers or civilians volunteered to go to the drop zone to take delivery of the supplies. Only when enemy fire stopped was the recovery of supplies accomplished. This slowed down to some extent the entire recovery and distribution process.

Food and medicine received by ARVN units were usually shared with

the local population. In return, the people of An Loc supplemented

the ARVN combat ration diet with occasional fresh food such as

fruit, vegetables and meat they gathered from their own gardens.

In addition, they assisted ARVN troops in administering first aid

and in medical evacuation and doing laundry for them. Never before

throughout South Vietnam had cooperation and mutual support between

ARVN troops and the local population been so successfully achieved

as in An Loc. Among the ARVN units that earned the most admiration

and affection from the city's population were the 81st Airborne

Rangers and the 1st Airborne Brigade. Both of these units not only

fought well and courageously but also proved particularly adept at

winning over the people's hearts and minds.

The food supply problem became critical because the civilian population that remained in An Loc also had to share the infrequent air- drops. Most of the An Loc population had been prevented by the enemy from leaving the city. At first, however, the enemy encouraged the population to evacuate when he began to encircle the city. But realizing that the ARVN defenders would eventually run into difficulties with supplies and medical treatment if they had the responsibility for local inhabitants, the enemy reversed policy and prohibited the civilian exodus.

At the time the first enemy attack began, on their own initiative,

some of the population of An Loc formed two groups and left the

city. One group was led by a Catholic priest and the other by a

Buddhist monk. Both groups moved south along Route QL-13 toward

Chon Thanh. When they reached Tan Khai, a village located about 10

kilometers south of An Loc, both groups were stopped by the enemy.

There, all able-bodied people, male or female, were impressed into

enemy service as forced labor to move supplies. The remaining,

children and old people, were all left behind to care for

themselves. Abandoned and lost, they soon became prey to hunger

and crossfire. They were finally saved from danger and death much

later when ARVN troops came to their rescue.

The Second Phase of AttackThe enemy's preparations for the second attack on An Loc was detected as early as 1 May when the 5th NVA Division headquarters relocated south to Hill 169. The following day, two regiments of this division, the E-6 and 174th, also moved south. They took up positions on Windy Hill nearby where they joined their sister regiment, the 275th, which had been there since 19 April after the withdrawal of our 1st Airborne Brigade. Next, the 165th and 141st Regiments of the 7th NVA Division left their blocking positions in the Tau 0 area and moved to the southern and southwestern sectors of the city. These movements were detected and reported quite accurately by Airborne Radio Direction Finding (ARDF). Together with the remaining units of the 9th NVA Division that continued to hold the northeastern portion of the city, this enemy redeployment was indicative of COSVN's determination to commit its entire combat force into an all out effort to take An Loc. Facing these seven enemy regiments poised around the city, the ARVN defenders numbered fewer than 4,000. Although most were still combat effective, at least a thousand had been wounded Morale was low since continuous enemy artillery bombardment kept the VNAF medivac helicopters away most of the time. Meanwhile, enemy deployments and an increase in enemy artillery and rocket fire against the city pointed toward an imminent all out attack.

The new plan of attack was confirmed and other details were

learned on 5 May when an enemy soldier surrendered to regional

forces patrolling on the southern defense perimeter. He was a

lieutenant from the 9th NVA Division. Interrogated, this enemy

rallier reported that his division commander had been severely

reprimanded by COSVN for failure to capture An Loc. In the

meantime, COSVN's Military Command had approved the 5th NVA

Division commander's request that his unit conduct the primary

attack instead of the 9th Division. He promised he would take An

Loc within two days, as he had Loc Ninh. The rallier

In the face of enemy intentions and known troop dispositions, the J2 and J3 at MACV began planning the use of B-52's to break the enemy's decisive effort. General Abrams, COMUSMACV quickly approved his staff's recommendations and provided III Corps with maximum tactical air support and priority in B-52 strikes for the defense of An Loc. The problem with using B-52's in tactical support, however, was precise timing, and to break the enemy effort the first requirement was to know exactly on what day this attack would begin. On 9 May, the enemy initiated strong ground probes and increased his artillery fire. The ground pressure abated within two hours but the heavy bombardment continued. To anyone knowledgeable about the pattern of enemy attacks in South Vietnam, this was undoubtedly an indication of imminent attack. The next day, the same pattern was repeated. Our U.S.-ARVN intelligence was completely accurate concerning the enemy's attack for 11 May and COMUSMACV adjusted his B-52 plan accordingly. Early in the morning of 11 May, after several hours of intensified artillery bombardment, the enemy began his ground assault from all sides. During the fierce fighting that followed, enemy forces made extensive use of the SA-7 missile against our gun-ships and tactical air. They also had better coordination between tank and infantry units, but ARVN soldiers stood their ground and systematically sought to destroy enemy tanks with their proven M- 72's.

As anticipated the enemy main efforts came from the west and

northeast. In these areas, enemy forces succeeded in penetrating

our perimeter. They seemed determined to push tanks and infantry

toward the center of the city where they would link up and split

our forces into enclaves. If this maneuver succeeded, the ARVN

defenders would risk defeat. The situation looked bleak enough

when, from their positions to the west and northeast, our forces

reported they were

In the meantime, VNAF and U.S. tactical air, which had been active since the assault began, methodically attacked enemy positions in both salients to the west and northeast. Their effectiveness was total; they not only helped contain enemy penetrations, they also inflicted heavy casualties on the entrenched enemy troops and forced some of them to abandon their positions and flee. During this day alone, nearly 300 tactical air sorties were used in support of An Loc. The tide of the battle turned in our favor as B-52's began their strikes at 0900 hours, when the intensity of enemy tank-infantry attacks were at a peak. Thirty strikes were conducted during the next 24 hours and their devastating power was stunning. By noon, the enemy's attack had been completely broken. Fleeing in panic, enemy troops were caught in the open by our tactical air; several tank crews abandoned their vehicles. By early afternoon, no enemy tank was seen moving. Those that remained in sight were either destroyed or abandoned, several with motors still running. In one area, an entire enemy regiment which had attacked the 81st Airborne Ranger Group was effectively eliminated as a fighting force. On 12 May, the enemy tried again but his effort was blunt and weak. A few tanks appeared but fired on the city only from standoff positions while infantry troops of both sides exchanged small arms fire around the perimeter. Despite deteriorating weather, U.S. tactical air and regular B-52 strikes continued to keep the enemy off balance around the city. The situation was one of stalemate and continued to be so during 13 May. Our chances of holding out in An Loc were increasing.

In the early morning of 14 May, enemy tanks and infantry attacked

again from the west and southwest. This attack was broken by

decisive B-52 strikes and ended by mid morning. Taking advantage

of the enemy's weakening posture, the ARVN defenders

counterattacked and regained most

This last attempt had cost the enemy dearly. Almost his entire armor force committed in the battle had been destroyed. Forty of these tanks and armored vehicles littered the battleground in and around the city. During the following days, the situation stabilized as enemy infantry troops completely withdrew outside the city and indirect fire on the city continued to decrease. There were indications that the enemy was now shifting his effort toward the 21st ARVN Division which was moving north by road toward the besieged city. An Loc had held against overwhelming odds. To a certain extent, this feat could be attributed to the sheer physical endurance of ARVN defenders and the combat audacity of such elite forces as the 81st Airborne Ranger Group and the paratroopers. Also commendable was the combat effectiveness of the territorial forces who fought under the strong leadership of the province chief, Colonel Tran Van Nhut. But the enemy's back had been broken and An Loc saved only because of timely B-52 strikes.

Relief from the SouthOn 12 April, the day after An Loc was attacked for the first time, the 21st ARVN Division closed on Lai Khe where it established a CP next to III Corps Forward Headquarters. Its initial mission was to secure Route QL-13 from Lai Khe to Chon Thanh, a district town 30 kilometers due south of An Loc. The division's advance unit, the 32d Regiment, had preceded the bulk of the division to Chon Thanh by trucks the previous day. The mission turned out to be an usually difficult one and its efforts encountered stiff enemy resistance from the beginning.

On 22 April, the road was blocked by the 101st NVA Regiment

(Separate) about 15 kilometers north of Lai Khe. As the 21st

Division moved north toward Chon Thanh, its advance was stopped by

enemy blocking

After clearing this road to Chon Thanh, the 21st Division initiated operations northward. It helilifted the 31st Regiment six kilometers north of Chon Thanh where this unit clashed violently for 13 days with the 165th Regiment, 7th NVA Division. During this battle, the enemy regiment sustained moderate-to-heavy losses inflicted by U.S. tactical air and B-52 strikes. It was reinforced by its sister regiment, the 209th, as the battle entered its terminal stage. On 13 May, the 31st Regiment finally overran the enemy positions. This extended the 21st Division's control of Route QL-13 to a point eight kilometers north of Chon Thanh.

Pushing northward, the division then deployed its 32d Regiment to

the Tau O area five kilometers farther north. It was in this area

that the hardest and longest battle was fought. The enemy was the

reinforced 209th Regiment of the 7th NVA Division whose fortified

blocking positions, arranged in depth, held the ARVN 32d Regiment

in check. I am convinced that there was no other place throughout

South Vietnam where the enemy's blocking tactics were so successful

as in this Tau O area. A Blocking position called "Chot",

generally an A shaped underground shelter arranged in a horseshoe

configuration with multiple outlets was assigned to each company.

Every three days, the platoon which manned the position was rotated

so that the enemy continually enjoyed a supply of fresh troops.

These positions were organized into large triangular patterns

called "Kieng" (tripod) which provided mutual protection and

support. The entire network was laid along the railroad, which

paralleled Route QL-13, and centered on the deep swamps of the Tau

O stream. This network was connected to a rubber plantation to the

west by a communication trench.

Despite its failure to uproot the enemy from the Tau 0 area, the 21st Division succeeded in holding down at least two enemy regiments, making them unavailable for the attack on An Loc. In the meantime, enemy pressure on the besieged city had made relief from the outside mandatory. One urgent requirement was to provide additional artillery support for both An Loc and the 21st Division's attack at Tau O. To achieve this, III Corps decided to establish a strong fire support base at Tan Khai on Route QL-13, 10 kilometers south of An Loc and four kilometers north of the embattled area of Tau O. For this effort, it employed a task force composed of the 15th Regiment, 9th ARVN Division, which had arrived from the Mekong Delta as reinforcement, and the 9th Armored Cavalry Squadron. On 15 May, one battalion of the task force began attacking north. It stayed east of Route QL-13, bypassing enemy positions. At the same time, another battalion and the task force command group made a heliborne assault into Tan Khai. The next day, the fire support base was established.

This new advance from the south soon drew the attention of the

enemy. By this time, his second major effort to take An Loc had

ended in failure. Shifting the effort south, on 20 May the 141st

Regiment, 7th NVA Division began attacking the fire-base at Tan

Khai. This attack lasted for three days but the defenders of Tan

Kai not only held but drove back all subsequent attacks throughout

the month of June. The presence of this base, which symbolized the

relief effort from the south, alleviated to some extent enemy

pressure on An Loc. Although only a partial success - Route QL-13

remained interdicted between Chon Thanh and An Loc - the southern

effort had achieved some of the effect intended. Concurrently, the

defenders of An Loc fought on, both

Mopping up Pockets of Enemy ResistanceAs of late May, re-supply by air for the besieged city became regular and efficient and the defenders were kept well supplied. This was a period of a relative lull in fighting, a respite for combat troops on the ground. Conversely, it was an ordeal for the American flyers and Vietnamese logisticians who had to struggle against great odds first to win the battle of technology and finally the battle of logistics. The fact that An Loc had held firmly to date in the face of ferocious attacks was not only because of sheer human endurance and courage on the ground and effective air support but because its defenders had been re- supplied. While the 21st Division was fighting in the Tau O area, the siege of An Loc was entering its final stage. After the second attempt to take the city and the subsequent attack on Tan Khai were unsuccessful, all three enemy divisions, the 5th, 7th and 9th, had suffered heavy casualties, estimated at about 10,000. Taking advantage of this respite, the weary ARVN defenders within An Loc passed to the offensive with the objective of expanding the city's defense perimeter. As ARVN troops became more aggressive, they increased patrolling activities outward and began clearing the remaining enemy pockets of resistance in the northern salient. By 8 June, the 48th ARVN Regiment had eliminated all enemy resistance in this area and by 12 June. the 7th ARVN Regiment had done the same in the western part of the city.

The situation in An Loc continued to improve thereafter. On 13

and 14 June, III Corps brought in one of the 18th ARVN Division's

regiments as reinforcement and fresh troops to replace the 5th

Division's weary combatants. On 17 June, the 48th Regiment of the

5th Division reoccupied Hill 169. From this regained vantage

point, ARVN observers were able to guide tactical air on targets of

enemy troop concentration

By 18 June, the situation had improved to the point that the III Corps commander declared that the siege of An Loc was considered terminated and released the 1st Airborne Brigade to its parent unit. And thus ended the enemy's scheme to create a capital city for the Viet Cong, and his threat on Saigon, our capital city, was eliminated. On 7 July, President Thieu made an unannounced visit to An Loc. From a high altitude approach, his helicopter suddenly dived and landed on the soccer field. He was accompanied by Lieutenant General Nguyen Van Minh, who as III Corps commander, visited the city for the first time since it came under siege exactly three months earlier. The president was greeted by an emaciated Brigadier General Le Van Hung, the hero of An Loc, whose eyes blinked incessantly under the glaring sun. Later the president confided jokingly to an aide, "Hung looked deceitful to me. Why do you think he kept constantly squinting and blinking his eyes?" The aide replied most seriously, "Why, Mr. President, General Hung had not seen sunlight for a long, long time." President Thieu then visited the city in ruins and the ARVN troops, to all of whom he promised promotion to the next higher rank. He also awarded General Hung with the National Order, 3d Class. III Corps spent the remainder of the year pushing the enemy back from An Loc and rotating troops garrisoned in the city. On 11 July, the entire 18th ARVN Division closed on An Loc, replacing the 5th Division. The 25th Division also relieved the 21st Division in its incomplete mission of reducing the enemy blocking force around Tau O. Finally, the 25th Division encircled remaining enemy strong points and neutralized them on 20 July.

During August, the 18th Division began operations to retake the

Quan Loi airfield but its efforts extended into September without

In the meantime, the grateful. people of An Loc City erected a monument dedicated to the heroic ARVN defenders. This monument stood amidst a cemetery especially built for the deceased troops of the 81st Airborne Ranger Group. The epitaph on the monument was contributed by a highly respected local elder. It read:

"An Loc Xa Vang Danh chien Dia

(1) COSVN Directive No. 43. (2) Tong Le Chan Base remained under ARVN control until April 1974. Following the cease fire of January 1973, the base was besieged and repeatedly attacked by elements of the NVA 7th and 9th Divisions for over one year before its final evacuation. It became a prominent case of enemy cease-fire violations and an eloquent testimony to ARVN combat heroism.) (3) A decision had been initially made to deploy this division to MR-l in an effort to retake the lost territory north of the Cam Lo River. But Lieutenant General Dang Van Quang, President Thieu's Assistant for Security was afraid the GVN would lose face if the PRG succeeded in installing itself at An Loc. Hence the decision was overturned and the 21st Division assigned to MR-3 instead.) (4) Literally: Here, on the famous battleground of An Loc Town The Airborne Rangers have sacrificed their lives for the nation.

|